Out of our five senses, vision is the most dominant in shaping our perception of the world around us. The brain works hardest to maintain a constant and coherent image of our surroundings in order to gather from it the necessary information to orient ourselves within them. Due to this ocular-centric mode of perception, it seems logical that human reasoning and imagination are also visually dominated, which generally reflects in our most prized cultural efforts, such as art and architecture. If we add to this notion our need to rigidly structure our immediate physical and ideological environments in order to make sense of the fundamentally chaotic nature of existence, it explains society’s proclivity to fall back on the sense of vision as the primary driver for cultural progress. What most architects and policymakers fail to take into account, however, is that this crude simplification of society and human nature comes with serious drawbacks, such as contributing to the global mental health crisis as well as the flattening of sensual experiences in cities across the globe.

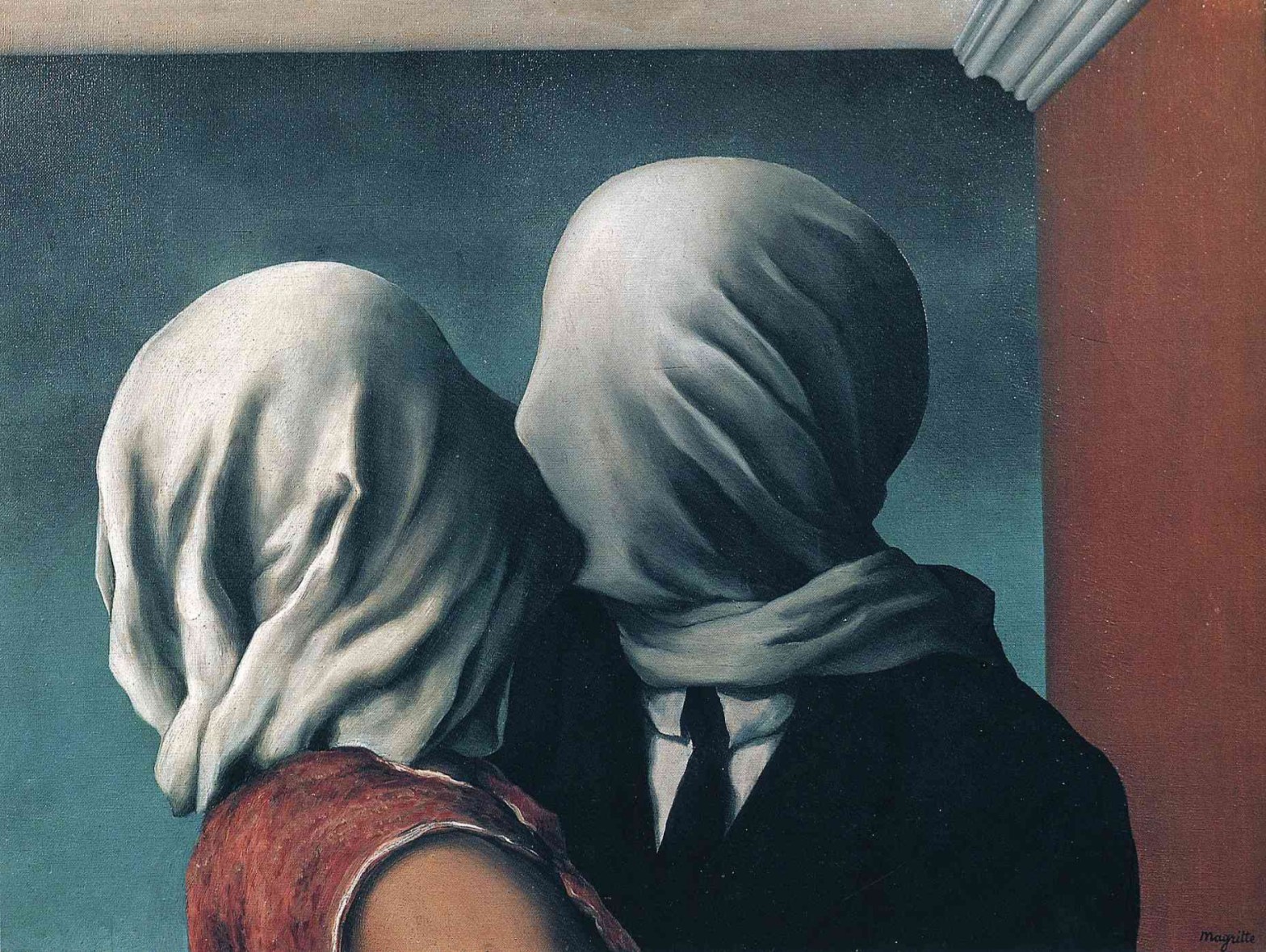

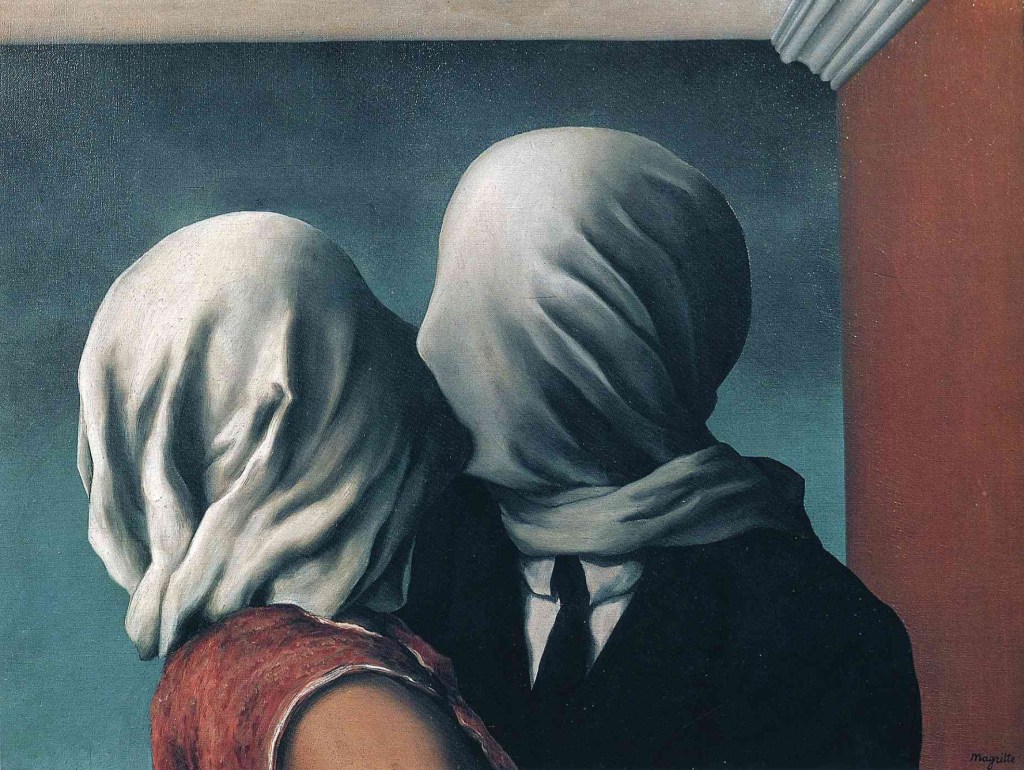

The Lovers by René Magritte, 1928

“My body is truly the navel of my world,” wrote the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, meaning that our understanding of Self is deeply rooted in our tactile experience of being-here. We need architecture to compartmentalize the vast and essentially meaningless mental space we all exist in in order to help us make sense of our place within the real world. Our physical environment acts as a mirror, reflecting our unfocused consciousness back to us, giving rise to our sense within it. Only if the existential human experience is established by and firmly rooted in the real world can the mind be free to venture out into the realms of dream and imagination. This seems to be the true purpose of art and architecture. It also explains why so many people can’t seem to escape their latent feelings of depression and dissonance. When someone fails to integrate their mind and body within a harmonious experience due to the distorted sensory signals emitted by the environment, self-identification becomes impossible.

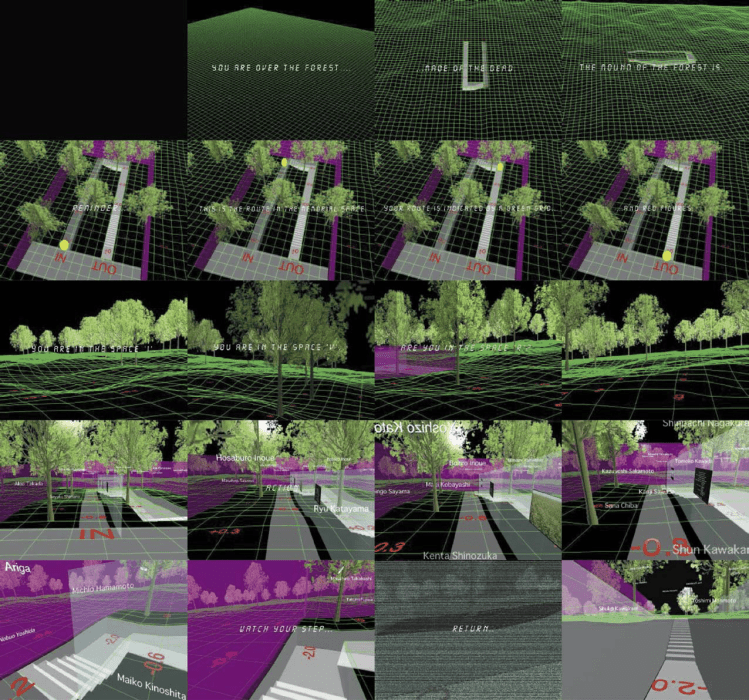

The goal for this series of essays will be to explore the interactions between humans and their built environment. Therefore, I felt it fitting not to open with a discussion about this-or-that architectural style but to take a more phenomenological approach to the origin of (Post-) Modernism as well as some of its derivates. I shall start with a short introduction of how the modern age has reinterpreted the multi-dimensional and multi-sensory nature of architecture before exploring some of the historical reasons for these developments. As I will argue in this first essay, the symptoms of modern architecture are threefold: First is the gradual transformation of architecture into mere semiotic constructs; second is the collapse of the temporal dimension in the creation and experience of space; and third is the concerning ocular-centrism — or the hegemony of vision over the other senses — that has befallen all aspects of modern life. As far as I’m concerned, all three have contributed to the dearth of sensuality and intimacy that is the signature of contemporary architecture.

M2 Building by Kengo Kuma, Tokyo, Japan – © wakiiii via Flickr

I SIGNIFICANCE

To recapitulate, Western architecture has seen numerous changes in the past two millennia, from the strictly geometrical systems of the ancient Greeks and their somewhat more loose interpretation by the Romans to the subsequent Romanesque and Gothic periods during the middle ages. While the term “dark ages” has recently come under scrutiny due to its implied value-judgment, it merely describes the efforts of the catholic church to restructure the cultural and political systems of Europe on a religious basis. The resulting scarcity of historical records from this time is the reason for its characterization as a period of intellectual and artistic poverty. Especially when it comes to culture, however, history tends to oscillate between the extremes such that most historically significant reactions inevitably become overreactions.

Gothic Architecture: Palace of Westminster, London, United Kingdom – © Manuele Sangalli via Unsplash

In the early 15th century, while Western Europe was still firmly anchored in the Gothic age of architecture, scholars and artists in Italy began to re-discover the teachings of their Greco-Roman predecessors. For the first time in recent history, art and architecture experienced a rebirth as intellectual pursuits, which is why this transitory period is now fittingly called Renaissance. Some of the most important architectural manifestos since Marcus Vitruvius wrote his Ten Books On Architecture around 27 BC came out of Italy during the 15th and 16th centuries. Since then, many more have been published, and as a result, architecture — if it hadn’t always been — has now solidified itself as much as a mental and abstract art as it is concrete.

Renaissance Architecture: Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, Italy – © Ray Harrington via Unsplash

This secular self-reflection initially helped to emancipate the arts during the dark ages but has since turned into a profound meaning crisis, and more specifically, a hyper-intellectuality which gave rise to a noticeable estrangement between architecture and its inhabitants. It has become increasingly difficult to decipher the hidden meanings behind architecture, which seems to have traded explicit symbols for implicit articulation. “Buildings, I’d always assumed, had an especially strong claim on reality,” wrote the author Michael Pollan. “Weren’t they supposed to be one of those things in the world that gets pointed to, and not just another one of the things that point?”

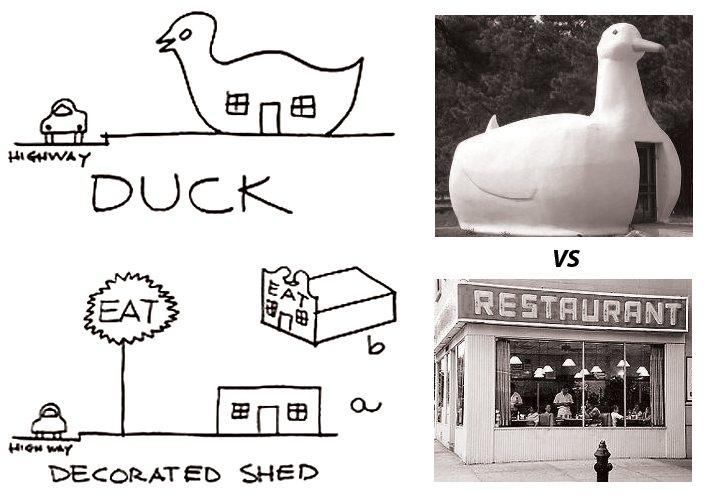

In other words, architecture used to derive meaning from itself rather than being a vehicle for external meaning. Even when a building wasn’t designed to reflect its specific use or location, its primary identity was to be defined by the articulation and formation of the genius loci.* That is until 1972, when Venturi, Scott-Brown, and Izenour published their seminal work Learning from Las Vegas, claiming that the modern age required a radical rebranding and redefinition of space. Space was to be knocked off its pedestal and, from now on, be subordinate to symbolism and ornament. Through studying the growing Mecca of consumerism and Postmodernism during the mid-20th century, the authors came up with the notion that modern architecture could, in fact, be anything and didn’t need to adhere to the rigid design principles of the past.

* Excluding some of the more egregious examples of certain powerful entities such as the catholic church who used architecture as a symbol of their power. You could argue that modern corporations have continued this tradition.

Las Vegas, USA – © Sung Shin via Unsplash

Their most significant conclusion was that modern architecture could be divided into the following two categories: The Duck, “where the architectural systems of space, structure, and program are submerged and distorted by an overall symbolic form,” and the Decorated Shed, “where systems of space and structure are directly at the service of program, and ornament is applied independently of them.” (For the name, they took inspiration from the Big Duck, a shop in New York selling ducks and duck eggs that was built in the form of, well, a duck.) Basically, a Duck explicitly represents what is inside the building by the way it looks, while a Decorated Shed does so indirectly through the use of signs and signifiers. This symbolism-over-space approach marks the shift of the architectural discourse from creating profound spatial experiences towards the mental science of signs.

Illustration of Duck and Decorated Shed from Learning from Las Vegas – © Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc.

The increasingly semiotic nature of Postmodern architecture is perhaps most clearly exemplified by the Deconstructivism movement during the 20th century. According to its founder, the French philosopher Jaques Derrida, architecture is to be viewed as a communication device; a mere metaphor for whatever social critique the architect wants to convey. Peter Eisenman, who is one of Postmodernism’s most significant architectural figures and highly influenced by Derrida, helped popularize these ideas. His designs question the conventional frameworks upon which architecture and modern life are built by explicitly seeking to divorce structure from program and replacing the latter with his own theories and ideologies.

In an interview with The Architectural Review, Eisenman went so far as to admit that he couldn’t care less about architects who worry about such minor details as the color or material of a surface since real architecture, which exists only in drawings, is merely an anti-material statement. In fact, the only reason why he actually constructed his buildings was that, otherwise, no one would’ve paid attention to the ideas behind them. For Derrida, Eisenman, and many of their followers, architecture is a form of language and a building merely its medium of expression.

That being said, it can be surprisingly difficult to work out the meaning behind these semiotic monuments beyond what the eye can see. Looking at Eisenman’s proposal for a new World Trade Center, for instance, you should be able to see that the two buildings are supposed to resemble the interlaced fingers of protective hands that evoke the feeling of presence and absence as well as containment and extension. Apparently, they are also a symbol of the site’s connections to the community, the city, and the world. Or at least that is what it says on the website.

Memorial Square World Trade Center by Peter Eisenman, New York, USA- © Eisenman Architects

A sign can be anything from a word to a gesture, or a building, as long as it communicates meaning to an interpreter. To give another example of this style, in which the building itself only serves as the expression of an often unrelated idea, the Nunotani Office Building in Tokyo was initially designed by Eisenman as a metaphorical record of the tectonic activity in that area. Further descriptions on the projects’ website state that the building aims to challenge the anthropocentrism and phallocentrism that traditionally inform the appearance of modern office towers “first by producing a building that is not metaphorically skeletal or striated but, rather, one that is made up of a shell of vertically compressed and translated plates; and, second, by producing an image somewhere between an erect and a ‘limp’ condition.” In other words, it’s a Duck. But is it a symbol for earthquakes, or the challenging of human egocentrism and patriarchal dominance-hierarchies, or maybe just a protest against d*ck-shaped skyscrapers? In 1992, an issue of the Progressive Architecture magazine described it as “a kind of cultural critique of architectural stability and monumentality at a time when modern life itself is becoming increasingly contingent, tentative, and complex.” Whatever it is, it’s clear that in the Postmodern age, form doesn’t follow function so much as it follows ideology.

Nunotani Office Building by Peter Eisenman, Tokyo, Japan – © Eisenman Architects

The Deconstructivist notion of challenging the established ideological systems that organize our world clearly has its place in the modern discourse. Sadly, it also seems to underestimate the intrinsic emotional value of architecture in particular. Regarding this rather misguided approach, Pollan comments, “making people uncomfortable is not merely the by-product of this style but its very purpose… But it seems to me it’s one thing to disturb people in a museum or private home where anyone can choose not to venture, and quite another to set out to disorient office workers or conventioneers or passersby who have no choice in the matter. And who also haven’t been given the chance to read the explanatory texts.” The resulting architecture might be valuable in its capacity as story-telling devices, but unfortunately, not as built structures.

While Pollan’s remark specifically refers to Eisenman’s Deconstructivism, his critique of the Modernists’ reliance on the “oceans of words that accompany prize-winning buildings today” can be applied almost across the board. As another case in point, take the Kunsthaus Graz by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, both part of the avant-garde architecture collective Archigram. According to the architects, the biomorphic structure “has the charm of a friendly mixed-breed stray dog, definitely highly questionable in terms of pedigree.” Apparently, the building aims “to reconcile a yearning to stand out as an object in its own right with that of wanting to service unobtrusively the works of art and installations it will be programmed to host.”

Kunsthaus Graz by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, Graz, Austria – © Marion Schneider & Christoph Aistleitner, CC BY-SA 2.5

In this case, the idea isn’t to challenge the status quo but to undermine the restrictive traditional frameworks that “slow down” cultural progress by exploding the aesthetic coherence of the buildings’ immediate environment. It is activism for activism’s sake, and while that technically makes it a Duck in the Venturian sense, the more fitting metaphor would perhaps be that of a Grenade.

To be fair, unlike Eisenman’s office building, the Kunsthaus was designed with a concrete purpose in mind since its high-tech façade is able to communicate with its surroundings by displaying certain information. With its performative features, the double-curved biomorphic skin has allegedly helped to turn the area into a cultural capital. Can it show a movie, you might ask? No… Does it somehow interact with the vernacular architecture of the UNESCO world heritage site that is the city of Graz? Also no. But it has LED lights that make cool patterns and basic lettering.

Kunsthaus Graz at night – © Zepp-Cam (first) and madbesl via Flickr (second)

Eisenman, on the one hand, was very critical of the theories published by Venturi and his colleagues, while Archigram seemed to be partial to their nihilistic and ephemeral notion of architecture. That being said, they all prove that, when it comes to the role that space occupies in our lives, they don’t know the half of it. Architecture exists in a higher reality of being, a state that is unattainable for the everyday object — and even for most art. Its one crucial characteristic is that most of us spend all of our lives in or around it, which is why, when other objects are being repurposed as semiotic vehicles, at least certain buildings still need to be granted the privilege of honesty.

Architecture needs to inspire, and not in the ordinary sense in which inspiration can come from any form of art, but in a much more universal sense. For space is not nothing. We inhabit space and are, in turn, inhabited by the images of it. While a painting or a sculpture, for instance, can inspire us, remind us, and make us think, we are always only faced with it. The pervading sense of unreality, of something artificial, prohibits the observer from fully dissolving into the experience. Art can show us the ideals of intimacy, desire, and repose, but only inhabited space can weave them into the very fabric of everyday life. Architecture, because of its omnipresence and because it challenges mind and body to an eternal dialog from the time we are born, doesn’t merely belong in the domain of matter but in the domain of what matters. As the French poet Noël Arnaud once wrote, “I am the space where I am.”

Street Photography captures the mundane everyday moments where person and place become inseperable – © Claudio Gomboli

In The Architecture of Happiness, Alain de Botton further observes that “architecture may well possess moral messages; it simply has no power to enforce them.” Inversely, if architecture rejects its ability to inspire in order to pursue some other arbitrary agenda, it inevitably does the opposite, by reinforcing our most cynic inner demons. Later in the book, de Botton recounts his experience of stumbling into a McDonald’s on Victoria Street in London: “The setting served to render all kinds of ideas absurd: that human beings might sometimes be generous to one another without hope of reward; that relationships can on occasion be sincere; that life may be worth enduring… The restaurant’s true talent lay in the generation of anxiety. The harsh lighting, the intermittent sounds of frozen fries being sunk into vats of oil and the frenzied behaviour of the counter staff invited thoughts of the loneliness and meaninglessness of existence in a random and violent universe. The only solution was to continue to eat in an attempt to compensate for the discomfort brought on by the location in which one was doing so.”

The architecture that constitutes the boundaries of inhabited space is often merely seen as a collection of objects in and around which subjective life takes place. But if we accept that we as humans are in huge part the result of our environmental conditions, it means that if our world is made up of nothing but dead matter without spirit or psyche, the same becomes true for us. In a strictly objective world, the subject gets lost and has nowhere else to turn to but nihilism and hedonism. After all, what’s left to live for once you realize that you are nothing but a short-lived material entity in a meaningless material world? Whether it’s fast-food restaurants, train stations, or office buildings, we encounter these types of places on a daily basis, much to the chagrin of those sensitive enough to notice how depressing they truly are.

McDonalds, Pine Brook, New Jersey, USA – © D. J. T. Sr. via Foursquare

U-Bahnhof Gänsemarkt, Hamburg, Germany – © NordNordWest, CC BY-SA 3.0

California DMV – © Omar Bárcena via Flickr

To drive home the point of how deeply misguided the Postmodernists are in assuming that a building is nothing but a potential sign, we need to look at what makes a sign meaningful and significant: First of all, the existence of meaningfulness necessarily carries the possibility for meaninglessness, which is that whose intrinsic meaning is inconsequential to the observer, because they either fail to decipher what the sign stands for, whom it stands in relation to, or both. In other words, one objectively recognizes a sign as such but doesn’t understand its definitive meaning. Insignificance, on the other hand, describes that which fails to convey even the slightest promise of meaning and is thus not recognized as a sign to begin with.

Therefore, architecture that is designed first and foremost as a sign needs to overcome two obstacles: First, it needs to be recognizable as meaningful beyond its primary function as a building and then be able to translate that meaning to an as-of-yet uneducated interpreter. Knowing this, the Postmodernists design buildings that disrupt the standard expectations we have of our environment in order to force us to stop and contemplate the reasons behind their extraordinary character. For instance, it doesn’t take an expert to realize that the Nunotani Office Building or the Kunsthaus in Graz don’t fit the norm; they are somehow different. This way, they achieve significance in their capacity as signs but aren’t yet meaningful to us as their promise of signification is only revealed in the accompanying texts. At this point, the building’s subjective value is determined by whether or not it does what it’s supposed to do and how it makes us feel. Ask your non-architect friends, and you’ll find that most people won’t even bother to think this far, at which point meaninglessness inevitably fades back into insignificance.

Modern semiotics often argues against the existence of such insignificant non-signs, as we are able to extract subjective meaning from anything, anywhere. And we can. But we don’t. Practically speaking, the world is too rich in stimuli that every object or building will be contemplated as powerfully meaningful beyond its earthly form. Herein lies the crux of the argument that forms the basis of the essay: There isn’t one definitive approach that reliably produces good architecture. However, problems always arise when a building’s utility or the quality of life of its inhabitants suffer because of the ideology-driven concessions that had to be made during the design process. Of course, compromises are always necessary, but what an unfortunate reality is spelled out by architecture that fails both as the functional expression of space as well as at communicating the abstract ideas behind it.

Binoculars Building by Frank Gehry, Venice, California – © Elizabeth Daniels via Phaidon Press

Many have questioned the responsibility of this approach, in which some seemingly arbitrary theoretical framework is used to justify dubious design choices. To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with the intellectualization of architecture. Not for nothing do we often speak of the mind palace or the proverbial fork in the road; places so rich in the most personal associations, their emotional depth is seldom achieved by actual brick-and-mortar buildings. Architecture does need to make us think and, most of all, dream. However, the school of phenomenology, which studies how we experience the world through our subjective modes of perception, is a much more useful tool for analyzing the interdependence of subject and space than its purely rationalist counterparts.

The problem isn’t one of visual style. Otherwise, any discussion of architecture would immediately fall apart once it reaches the moral impasse of judging individual taste. Nor is it concerned with the viability of Deconstructivism or any other philosophy. Instead, the question needs to be, who are we designing for, and what are the incentive structures that underlie the architectural practices of the 21st century?

Mind Palace – © Gary Ng via Instagram (@garyfive)

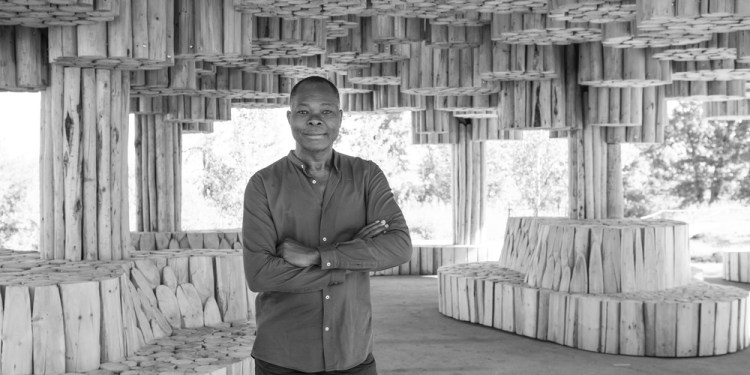

Designing a building or a public square used to mean envisioning oneself within an imaginary space, moving through it, and conjuring up the architectural elements before the mind’s eye. Some of these intentions were concerned with creating beautiful spatial experiences, while others aimed to serve and improve the lives of the people who use them. The fruits of these mental exercises include all kinds of different buildings from Gaudís’ Sagrada Familia in Barcelona to Francis Kérés’ humble schools in rural West Africa. Both valuable and beautiful in their own right. Nowadays, however, the goalposts seem to have shifted away from creating these extraordinary structures and towards carefully engineering the most attractive visual commodities.

Contrary to popular belief, it may not be due to the social and technological changes of the modern age, along with its increasing demand for efficiency and sustainability, that architecture has developed into these shallow caricatures of itself. These factors draw closer and closer circles around the feasibility of new projects, but they do not inherently restrict the architects’ ability to design a good building. Once the most relevant social and environmental issues have been addressed, however, the architect, along with the client, usually chooses one more measure of success for the project. Best-case scenario, this should be to improve the quality of life of the people who use it, but these days more frequently, it seems to be its ability to be distributed through digital media. These buildings look enticing, but not particularly user-friendly — and they don’t try to be. They are visual commodities; a literal product that is being sold, not as three-dimensional architecture, but at best as a vehicle for whatever social critique or creative phantasy the architect wants to convey, and at worst as a tool to garner as much short-term attention as possible. As a result, this “photogenic architecture” is designed as a series of visual snapshots intended to be presented as such to the public.

Compare these two public spaces:

French Quarter, New Orleans, USA – © unkown

Hochhausensemble Hagenholzstraße by Max Dudler AG, Zurich, Switzerland – © Stefan Müller

By now, Eisenmans’ complete rejection of the built form seems almost righteous since he’s at least honest when he says that he doesn’t care about the building itself. Today, architects seem to stamp the most altruistic intentions on the most self-serving architecture, focussing more on the quality of their renders and lyrical ramblings than on the first-person experience of their buildings. Both in art and architecture, fame does not equal success, and profound meaning is not measured by the number of likes on social media. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with wanting to increase one’s public visibility, problems always arise when the measure of success informs the method. As Pallasmaa wrote over 30 years ago, “The architecture of our time is turning into the art of the printed image fixed by the hurried eye of the camera.”

Glass Pyramid in front of the Lourve by I.M. Pei, Paris, France – © Paul Stamatiou (Twitter: @stammy)

II TIME

Photos, renders, and perspective drawings only give one singular viewpoint, which at its center depicts space as it would’ve been perceived by an observer, while at the margins, the image becomes heavily distorted and entirely non-representative. Once the person shifts their position relative to the object, the initial perspective is rendered useless. Though necessary to convey vital information about the project, they cannot adequately represent it. They flatten time and distort space.

This phenomenological inadequacy was recognized by the Modern Movement during the early 20th century, which formally expanded the three-dimensional vision of space by adding the fourth dimension of time. While space was still paramount, a new wave of upcoming architects shifted towards designing for visual variability as space was to be experienced along a spatial-temporal axis as opposed to statically from one single point of view. This new architecture, which Le Corbusier famously called promenade architecturale, considered the building from all possible modes of experience, such as walking through it, driving by it, lingering outside it, and so on.

In order to solve the problem of spatial-temporal representation in a culture that still heavily relied on two-dimensional photographs as a means of mass communication, modern architects started designing winding staircases, ramps, and visually stimulating vantage points to create a sense of movement from a flat photo or drawing. This imagined movement was supposed to represent the flow of time as it relates to the experience of moving through the depicted space. The results were the generous use of glass and the design of the simple yet intricate spaces we now recognize as the signature of early Modernist architecture. It turns out, however, that there is a difference between the unraveling of natural movement through space and time and its mere representation through visual tricks.

Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier, Poissy, France – © Scarletgreen, CC BY 2.0 (first) and a-m-a-n-d-a, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (second) and Renato Saboya, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (third)

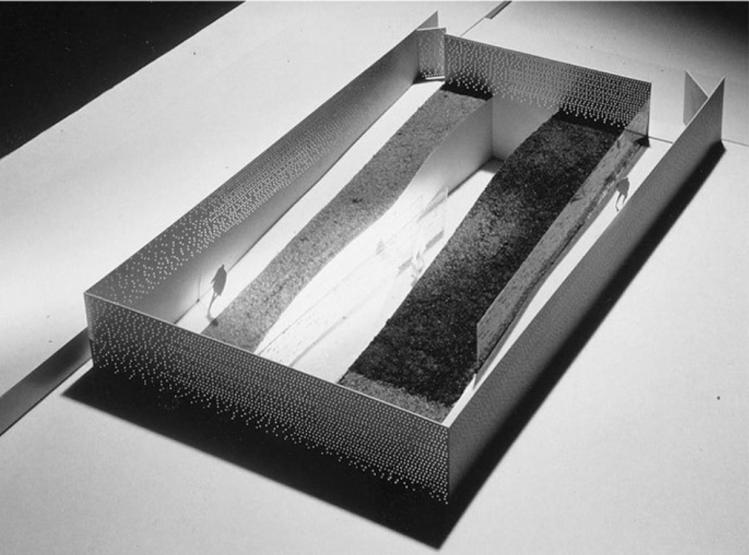

In order to better understand the concept of time as it relates to the architectural experience, imagine a landscape garden like Stowe Gardens in Buckinghamshire, England, and compare it to the Baroque garden of Herrenhausen in Hannover, Germany. In the former, time plays a crucial role in unraveling the subjective experience as the individual is physically moving through space, stumbling over hidden alcoves and picturesque views while exploring the as-of-yet-unknown environment. In the latter, time is frozen in order to preserve a perfect, in this case, geometrical image. In Herrenhausen, the dichotomy between the design and the actual experience becomes especially apparent: While the true nature of the landscape garden couldn’t possibly be depicted in one single or even a series of photographs, the full beauty of the Baroque garden can only be appreciated from a birds’-eye-view. Once a subject is introduced at ground level, the perfect geometrical shapes lose their significance, and the whole illusion immediately falls apart. Conversely, the fact that the experience of the landscape garden is inseparably connected to its temporal dimension forces the visitor to observe themselves within the full four-dimensional space-time continuum of the garden.

Elysian Fields at Stowe Gardens – © Hugh Mothersole via National Trust Images

Herrenhäuser Gärten, Hannover, Germany – © Herrenhäuser Gärten

The example is poignant because it illustrates a concept that is much harder to see in actual architecture: A garden is the literal extension of nature and interacts with humans in much more sensual ways than inanimate objects. Architecture, on the other hand, is mentally conceived and placed into the world, remaining a separate entity if no effort is made to integrate it with its surroundings. The architectural equivalent to the Baroque garden is designed as a series of images that, in the end, make up an Object that is entirely independent of the subject and its environmental context. In contrast, a landscape garden and what Japanese architect Kengo Kuma calls Anti-Objects, are designed as a series of experiences. Object-oriented architecture is based on arbitrary geometrical systems, while subject-oriented architecture is mainly concerned with how a subject moves through and experiences space.

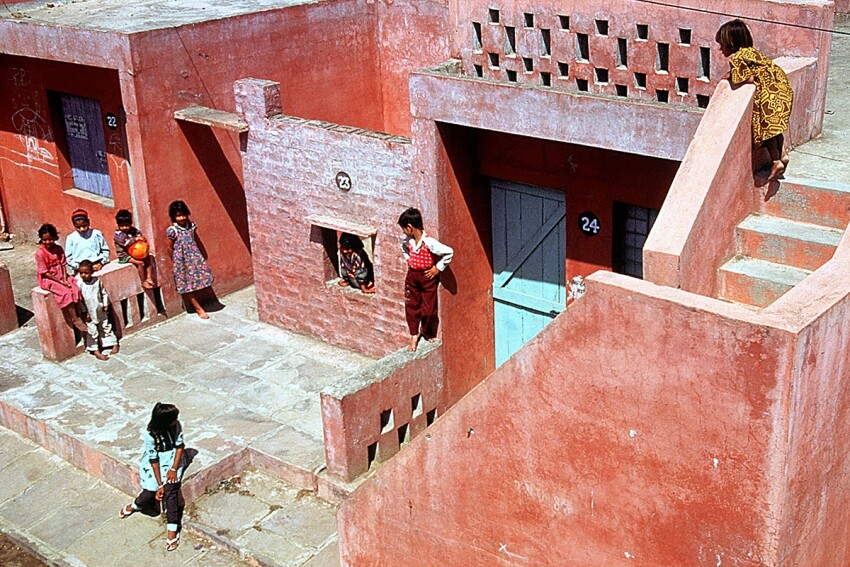

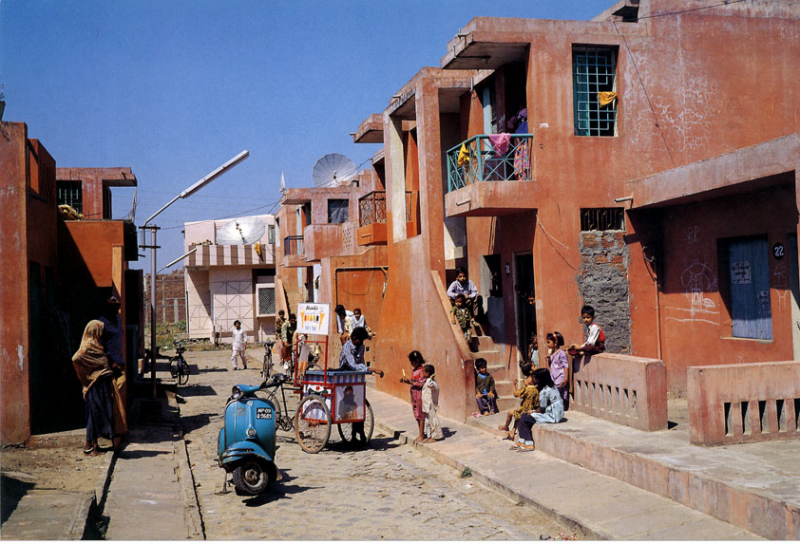

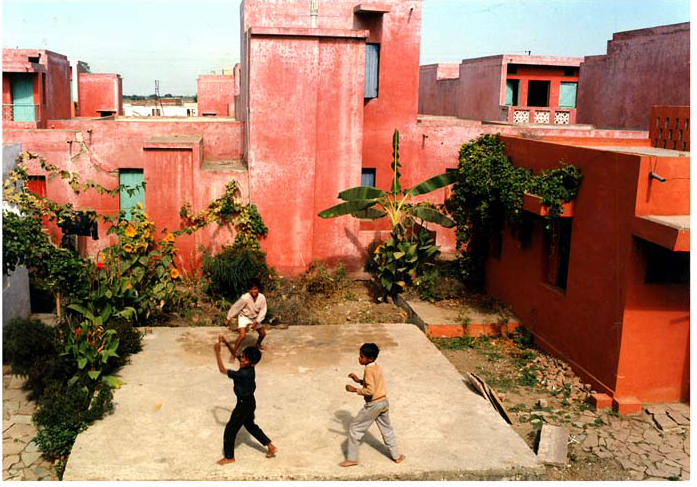

With the example of the two gardens in mind, specifically the idea of space in flux, the following two settlements illustrate similar concepts regarding the interdependence of space and time on a macro-level. The first is a famous experiment in efficiency and modular building aimed to counteract the living crisis in 20th-century Germany. The Bauhaus Siedlung in Dessau-Törten was designed by non-other than Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius himself and included 316 individual homes built between 1926 and 28. The second settlement is equally concerned with providing affordable living space, only on a much bigger scale. Originally intended to house a population of 60.000 (now more than 80.000) in over 6.500 residences, Aranya Low-Cost Housing in Indore, India, was commissioned in 1983 to provide urban dwelling for the economically weaker classes. Although constructed 60 years apart by cultures that couldn’t be more different, their shared motif of solving an imminent housing problem makes them eligible for comparison. What’s more, both Walter Gropius and Balkrishna Doshi, who initially designed 80 model units in Aranya, shared the same maxim that architecture is essentially the art of lifestyle design — but what different lives they must have imagined.

Object-oriented architecture in Dessau-Törten, Germany – © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Subject-oriented architecture in Aranya, Indore, India – © Vāstu Shilpā Foundation

While the Bauhaus Style under Gropius aspired to the rationalization of building which resulted in the rigorous Functionalism that made the school so popular in post-WW1 Germany, Doshi had the distinct advantage of growing up in India, coupled with an apprenticeship under Le Corbusier in the early stages of his career. Through his Eastern upbringing and later working alongside the pioneers of Western Modernism, such as Corbu and Louis Kahn, he developed a thorough understanding of how people inhabit space, independent of culture and location. Doshi strongly believes that participatory involvement in the process of building homes is fundamental for creating a sense of belonging. Thus in Aranya, each plot was outfitted with a plinth and a service core, connecting it to the water and electrical grids. From there, the architecture was able to grow organically, according to the needs of its inhabitants. Erect a couple of walls, add a roof, and you have a new room. This way, the architecture becomes “an unending chain of construction and destruction, where the present is only a phase in transition.” An unthinkable sentiment in the West.

Object-oriented architecture in Dessau-Törten, Germany – © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Subject-oriented architecture in Aranya, Indore, India – © Vāstu Shilpā Foundation

In Western culture, time is absolute, and concepts such as punctuality, deadlines, and appointments structure its linear flow. In Hinduism, on the other hand, time is cyclical and relative. Without knowing about relativity, the ancient Hindus believed that the duration of time differed between the worlds and that the soul would experience time and no-time all at once due to its transcendent relationship to the cosmic rhythm. In Aranya, the concept of relative time expresses itself in the innumerable niches, corners, and corridors that change the very nature of time as one moves from one spatial experience to another. By rounding a corner or climbing a flight of stairs, time abruptly slows down or speeds up, and space is experienced proactively as one is able to live “at either the pace of a village or small town, or at that of a neighbourhood on the fringe of a metropolis.“

Once rigidity, as experienced in Dessau-Törten, is transcended, the full ambiguity of life opens up. When even the concepts of space and time become distorted, other extremes have no choice but to loosen their grip on reality. In Aranya, outdoor staircases, shared landings, and extended thresholds blur the lines between inside and outside. Here, where time is no longer dictated by clocks, solid meets void, and finite becomes infinite. Clearly, there is value in reducing uncertainties, but if one goes too far and kills off any possibility of spontaneous discoveries or unexpected encounters, life soon becomes very dull. Architecture, therefore, needs to allow for those irregularities, even at the cost of sacrificing certain aesthetic ideals. While in Aranya, freedom of movement is encouraged, in Dessau-Törten, it is strictly regulated. You either move along the axis of the street or laterally to it in order to enter your home where life is neatly tucked away, like drawers that the people are stored in when they are not at work. There is no up and down, no back and forth, no interaction. Only in Aranya the architecture is given a chance to come to life.

Movement, chance, and the emphasis on spiritual values over material ones are not functions of financial means or technological sophistication but of time. In this way, time-sensitive architecture not only promotes intimacy on a micro-level but might help to prevent the sociocultural disintegration we experience in the West.

Object-oriented architecture in Dessau-Törten, Germany – © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Subject-oriented architecture in Aranya, Indore, India – © Vāstu Shilpā Foundation

As an architect, imagine returning to a site years after the project has been finished and seeing that nothing has changed. While in other cultures, life seeps into every corner of private and public space, architecture in the West has become increasingly transitory. Like hermit crabs, we move out of our childhood homes and henceforth never develop the same relationships with our environment. Although very poor by Western standards, the people in developing countries still understand the value of belonging and how our physical environment acts as the root of cultural and social cohesion. Come back to a site in such a place, and you’ll witness the unique ingenuity of poverty and how these people will have changed the initial design in order to suit their specific needs. This is because they have accepted the building as their own, as part of their life, and have given it its own identity that will grow alongside them. That building will now live forever in the memories that are inseparably bound to it. In comparison, the Western notion of perfection becomes utterly meaningless.

The Back to Rio project is painting the streets of some of the most notorious favelas in Rio de Janeiro

© The Favela Painting Foundation

Still, it may not be intuitively obvious why an abstract concept such as space-time should have any relevance in architecture, let alone in our daily lives. In physics, space and time are the informational components of a four-dimensional system, meaning that in the vast context of the universe, four coordinates are required to describe an object in space and time. Architecture, however, since it is usually immovably located somewhere on earth, can be sufficiently characterized by its unambiguous spatial identity. As a result, the physical location of a building, as well as its proportions and dimensions, are always carefully considered, while the variable of time is commonly neglected. This spatial identity might be enough to satisfy architecture’s basic purpose of providing shelter, but it fails to address its never-ceasing emission of sensual cues at every level of human perception. To put it in more phenomenological terms: words such as static and sterile are sometimes used to describe the impression that newly built architecture can have on us, but they cannot persist over time. When a building ages and starts to wear the traces of its use boldly on its skin, it develops a unique identity. A natural patina such as is characteristic of materials like wood, stone, or concrete, anthropomorphizes the architecture into something resembling a conscious being.

Acorn Street in Beacon Hill, Boston, USA – © unknown

As humans, we age over time, our personalities change, and we learn to see other people as the sum of their life experiences as well. Imagine someone whose personality never changes throughout their life; someone that remains static in their views and attitudes, unable to change according to the circumstances of their environment. We wouldn’t trust such a person. Similarly, architecture that seems unaffected by time entirely rejects the possibility of any emotional connection. This often happens when the architect insists on upholding the virgin state of a newly finished project under all circumstances. Attempting to freeze this fragile moment in time, no resources are spared to maintain the illusion of perfection, imprisoning the architecture in the realm of beautiful yet meaningless objects. Examples of this are the use of age-resistant materials or the compulsory whitewashing of early Modernist architecture. Without the ability to change, the architecture remains static and sterile. What’s more, when a subject enters into such a setting, its body and spirit become objects themselves, mere spectators, unable to interact with or change the environment around them.

In an attempt to compare apples to apples as much as possible, take Gropius’ iconic Bauhaus Building (1925-26) and Doshi’s Indian Institute of Management (1977-92) and see for yourself how one of these projects has been allowed to register the passing of time by letting nature reclaim its once pristine site — and the other hasn’t.

Bauhaus Building by Walter Gropius, Dessau, Germany – © Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Indian Institute of Management by Balkrishna Doshi, Bangalore, India © Sanyam Bahga

Further elaboration on the emotional significance of architecture that fully explores this four-dimensional spectrum of human experience is given by the French philosopher and phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard. In his book The Poetics of Space, Bachelard reminds us that it is, in fact, not an innate quality of time that gives a memory its emotional significance but its irreversible attachment to a certain place. In other words, it is not its point in time that immortalizes a moment into a memory, but its physical location. “In the theater of the past that is constituted by memory, the stage setting maintains the characters in their dominant rôles,” Bachelard writes. “Here space is everything, for time ceases to quicken memory… To localize a memory in time is merely a matter for the biographer and only corresponds to a sort of external history… For a knowledge of intimacy, localization in the spaces of our intimacy is more urgent than the determination of dates.”

What differentiates these theaters of the past that so unmistakably reverberate with the sounds of our most intimate memories is their ability to absorb whatever emotion we felt at that moment. Without actively trying to, we dissolve into the spaces we inhabit, allowing the identities of Self and Space to fuse together. By establishing a save-space for our dreams, the Home allows us to open up and explore the world beyond without the fear of losing ourselves. From the time we are toddlers, we trust these places with our subconsciousness while the consciousness ventures out in search of meaning and growth. In turn, we allow them to physically imprint themselves on us in the form of physical habits — or as Bachelard puts it: “after twenty years, in spite of all the other anonymous stairways, we would recapture the reflexes of the ‚first stairway,’ we would not stumble on that rather high step.” The theaters of our lives defy emotional insignificance due to their capacity to grow old alongside us. As their walls crack, our faces wrinkle, and does the creaking sound of old wood not remind you of an aching back?

Casa Barragán by Luis Barragán, Mexico City, Mexico – © La Casa Barragán (first) and Rene Burri (second and third)

There is an undeniably human aspect to patina which is just one of the ways in which architecture transcends its euclidean coordinates in space. Nature is not static, and in order to connect to people, architecture, too, needs to be able to evolve over time. These days, however, the gradual displacement of natural materials and honest craft isolates us within the places we used to inhabit. As its multi-sensory plasticity fades, architecture becomes locked away in the cold realm of mental abstractions that is the domain of Postmodernism. Society’s obsession with focussed vision has reduced the ideal of aesthetic perfection to a predictable image that is nowadays almost exclusively used to manipulate people into engaging in certain behaviors or buying certain products.

In a world where an infinite amount of images and videos are instantly accessible to us at all times, it’s no wonder that our other senses have become increasingly desensitized. Our hedonistic attitude towards visual stimuli has led us to forget the multi-sensory nature of true intimacy. After all, in times of intense passion, vision is often repressed in order to fully immerse oneself in the sensuality of the moment.

The Lovers by René Magritte, 1928

III VISION

One doesn’t need to look far in order to see the plethora of modern illnesses this poor diet of multi-sensory stimuli has helped to spawn. Noise pollution, for instance, which is a result of planners failing to take into account the auditory aspects of urban environments, or the growing popularity of windowless façades, have contributed to the high incidence of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and sick building syndrome (SBS),* not to mention poor sleep and overall health. Especially the modern office has transformed into something like a cast for the brain. With their fluorescent lighting, sterile interior, and recycled air, these environments do their best to limit the variability of outside stimuli in order to spare costs while increasing productivity. This kind of sensory deprivation is not too far removed from various forms of psychological torture used on prisoners in order to mentally break them.

White Room Torture consists of the detainee being held in a brightly lit, white cell that is completely shut off from any outside sounds. Former prisoners have reported the loss of personal identity and psychotic breaks, once again confirming Pallasmaa’s notion that our sense of Self is deeply intertwined with our sensual relationship with the outside world. Like the muscles in a broken leg, the brain’s plasticity decreases if it’s not adequately stimulated, and the sensory sterility of modern architecture is becoming a deeply concerning issue for mental health.

The scents and sounds of urban environments have been most affected by this. Nowadays, far more effort is being exerted to minimize natural odors and unwanted noise than on how these stimuli can be used to enrich the experience of space.

*That said, a growing body of research, as well as advancements in technology and building design, might be responsible for the decline in cases of SBS in recent years.

Typical Office Interior – © Pexels

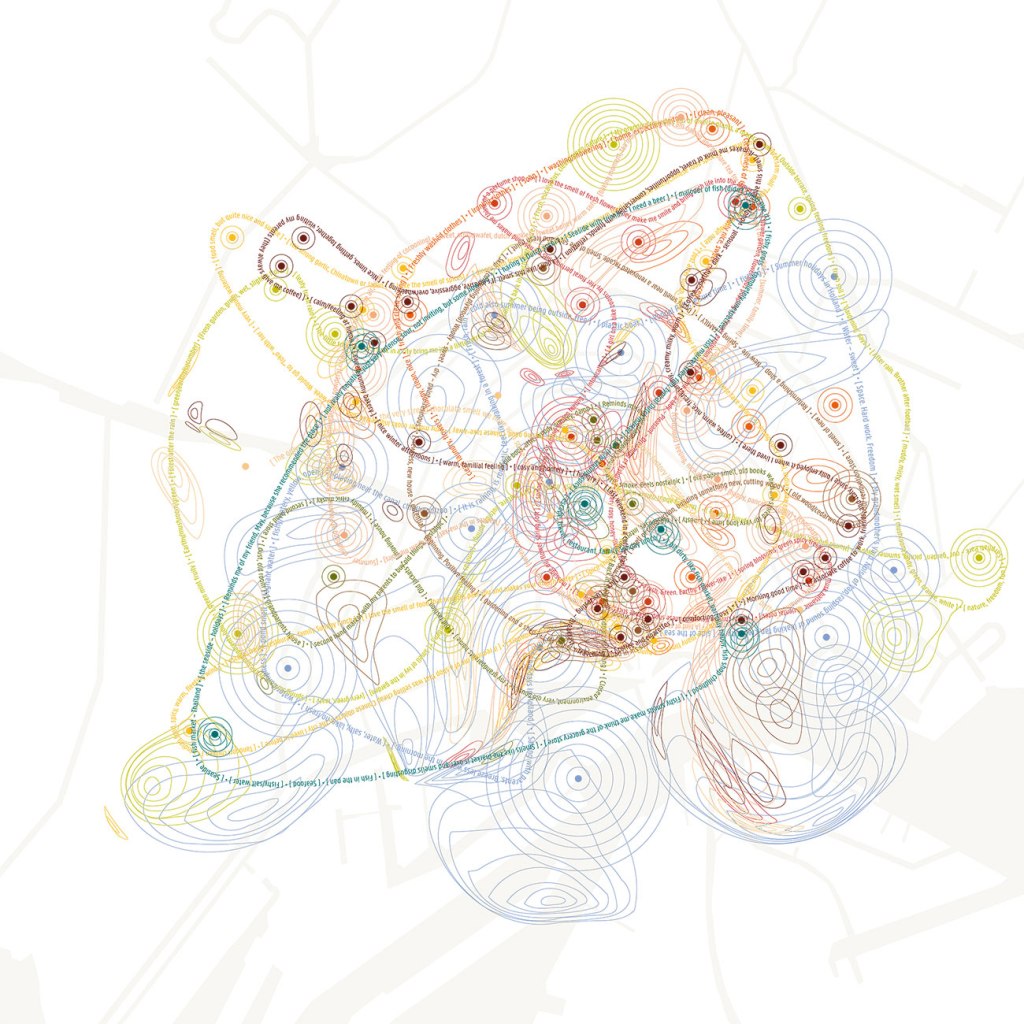

Scent is an especially effective trigger of emotions and, unlike the other senses, hits you with an urgency that transcends language and thought. “Hit a tripwire of smell, and memories explode all at once,” says Diane Ackerman in A Natural History of the Senses. The odors of our past are usually well hidden in the weeds of our memory, but even a momentary smell will shake your entire perception of space and time to the core. Like a land mine, the scent of a long-lost lover might suddenly explode in memories of passion, intimacy, and pain. Likewise, certain smells will elicit daydreams about childhood summers, family meals, and falling asleep under the great oak in your grandmother’s backyard.

Next time you find yourself in a new place, try to experience your environment through its unique blend of smells: close your eyes, and you’ll be torn apart by the desire to follow the scent of warm waffles in the market, chasing a moment of peace next to the canal that still smells like fresh rain, and dreaming about getting lost in the old bookstore on the corner.

Legend has it that during the construction of a mosque, Islamic builders used to mix rose water and musk with the mortar so that the sun would heat up the bricks and release their fragrance, intensifying the religious experience within.

Smellmap of Amsterdam – © Sensory Maps

In the West, we might be inclined to compare the scent of a mosque to the sound of a cathedral. Sound has the ability to carve a volume into the dark, such that we can tell the difference between a gothic cathedral and a romanesque church upon the first note of the organ filling the void. Like the sense of smell, hearing is an intensely personal experience that centers you within the architectural space. “Sight isolates, whereas sound incorporates,” writes Pallasmaa, “I regard an object, but sound approaches me; the eye reaches, but the ear receives. Buildings do not react to our gaze, but they do return our sounds back to our ears.”

Every place has its own sound, and without using our eyes, we are often able to accurately assess its vastness, as well as the ideals its echo wants to impart. Whether it’s the transitory feel of a busy street, the industrious vibrancy of a market, or the womb-like intimacy of a home, the ears are often the far more educated interpreter of spatial moods than the eyes. The bare urban landscapes of modern cities, on the other hand, built for cars and commerce, carry the acoustic harshness of an unfurnished home — only without the possibility of life taking root inside them.

Busy Market – © Jessamine via Dreamstime.com vs. Busy Street – © Akash Rai via Unsplash

The sense of touch is our most intimate way of interacting with our environment. In an increasingly abstract world, where everything from matter to meaning can be questioned, touch is what inevitably brings even the most agnostic among us back to reality, for its intimate nearness makes it the hardest sense to deny. The loss of tactile depth, however, that so carelessly has been allowed to spread from strictly utilitarian architecture to even our most sacred hiding places may eventually result in the complete dissociation of people from their environment. Just consider the horrific effects that the mandatory isolation and deprivation of human touch during the COVID-19 pandemic has had on peoples’ psychology. Besides physical ailments due to the inevitable changes in lifestyle, stress and anxiety have shot up during the lockdowns when not only touching other people but even accidentally making contact with a door handle or handrail became unsanitary and forbidden. Pallasmaa emphasizes the significance of touch in the architectural experience, writing, “the door handle is the handshake of the building. The tactile sense connects us with time and tradition: through impressions of touch, we shake the hands of countless generations.”

As a result of censuring this tactile relationship between ourselves and reality, people have developed addictions to drugs, food, or cheap entertainment as coping mechanisms for their isolation and have since over-compensated for the lack of physical and emotional contact.

© Andrew Cashin via MTA New York City Transit, CC-BY 2.0

The haptic monotony of modern materials is degrading our physical environment to the level of a stage set — an image only to be seen, but not to be felt, lest the illusion loses its credibility. Just by looking at an object, we are usually able to gain a sense of its material properties, such as weight, smoothness, and density. Different materials carry specific meanings, which we interpret as intrinsic characteristics of that material. In other words, we ascribe an identity to an object based on the meaning we project on its material. Wood feels warm and comfortable, while metal is cold and distant, etc. Take away this emotional depth, and you’re left with the outermost layer of physical reality, completely stripped of sensual nuance. Only if we re-commit ourselves fully to this sensual reality can we, like Goethe, “see with the caressing eye, feel with the seeing hand.“*

*In my opinion, this is a more accurate translation of the original line “Sehe mit fühlendem Aug’, fühle mit sehender Hand,” than the more common English translation.

Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright, commonly considered one of the most important architects of the Modern age due the haptic nature of his architecture – © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

But how exactly is the experience of architecture related to our senses? Today, a growing body of research emerging from the field of cognitive neuroscience is attempting to prove what the phenomenologists have long suspected: The multi-sensory nature of the human mind does not separate subjective meaning from experience. Not only that, but we infer meaning based on past experiences, which in turn changes our perception of future events.

The majority of architecture that is designed with this new scientific evidence in mind, however, still either employs a uni-sensory approach or attempts to prompt a multi-sensory experience by merely layering different stimuli on-top of each other. Synaesthetic design (Pérez-Gómez, 2016), for example, is a popular practice that attempts to establish a more congruent experience but does so by merely pairing certain engrained associations, such as high-pitched sounds with tiny, fast-moving objects. This strategy is often used to mask the artificiality of a setting, like a flowery scent being introduced into an environment with fake plants or the recording of engine sounds being played through the speakers in an electric car. In a 2020 review article titled Senses of place: architectural design for the multi-sensory mind, experimental psychologist and researcher Charles Spence argues that the concept of synaesthetic design should be replaced by a more fine-tuned approach that is based on cross-modal correspondences, instead. Essentially, the question isn’t how many senses we need to stimulate in order to create an integrated experience of Self but rather to which extent the senses communicate with each other, influencing perception on a far more interdependent level than previously assumed.

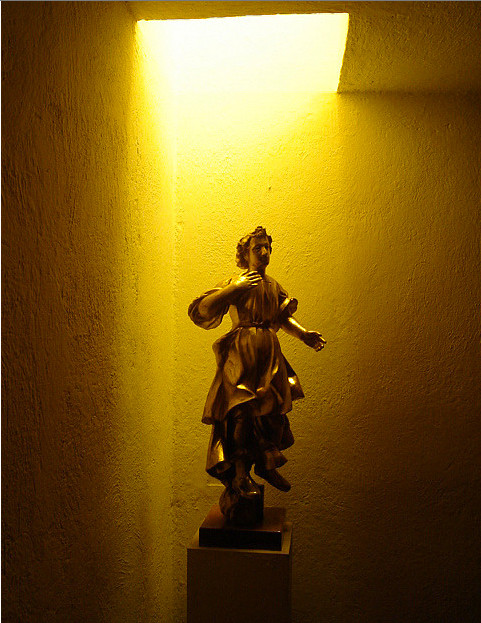

There is, for instance, plenty of research examining the relationship between lighting color and perceived thermal comfort as well as interior surface hue and mood. The Mexican architect Luis Barragán famously used to pin pieces of differently colored paper on the walls of his home in Mexico City in order to examine them under different lighting conditions before deciding on the appropriate color for that wall. To think that these considerations were exclusively visual is missing the point. As a master of the interplay between color, material, and light, Barragán is able to create manifestations of light that seem as dense as any other matter. They make you feel their warmth and weight on your skin in far more tangible ways than your eyes can perceive.

When visiting Casa Barragán in Mexico City, I stepped into the minimalistic dressing room on the first floor and was struck by a beam of the warmest orange light spilling out from a narrow staircase tucked away behind the back wall. I was immediately drawn towards it, fully expecting to feel the light touching my skin as if it were a vail, announcing some higher reality behind the tinted glass door that led onto the roof terrace.

Casa Barragán Interior – © Charles Avignon (first), Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán A. C. (second), Rene Burri (third), LrBln via Flickr (fourth and fith)

Research further suggests that it is possible to elicit certain sensory responses by artificially introducing the corresponding stimulus. However, an essential factor in whether or not we perceive environmental stimuli as positive is their congruency — or their likelihood of occurring together in nature.

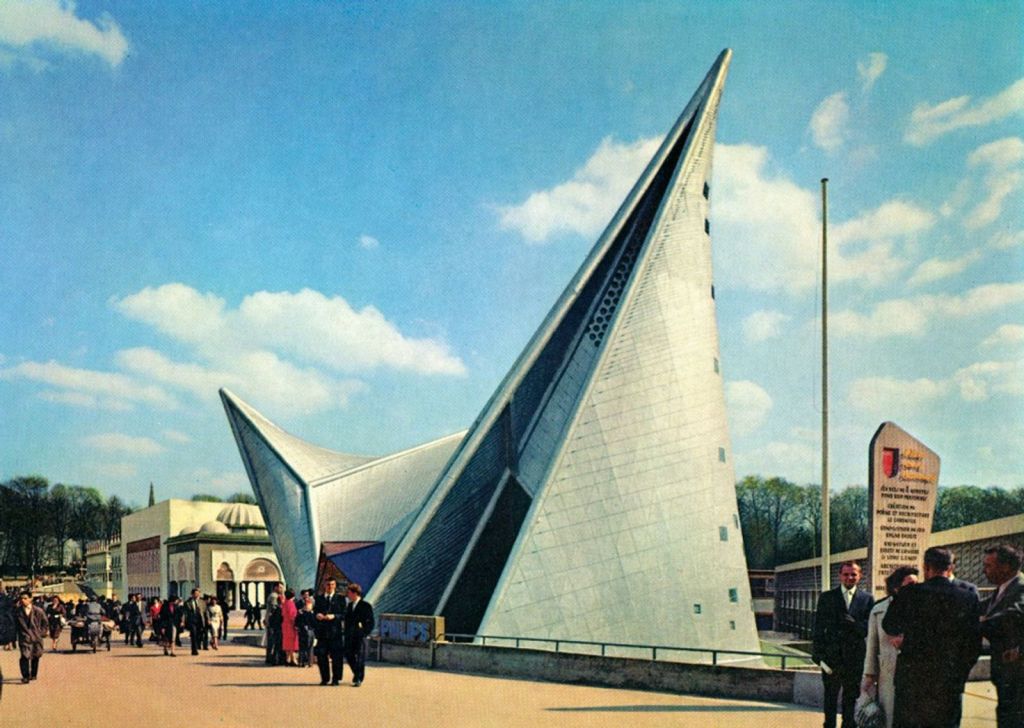

When the Dutch electronics manufacturer Philips commissioned Le Corbusier to design a pavilion for the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, the objective was to create an audio-visual experience that the world had never seen before. Working alongside the architect Iannis Xenakis and the composer Edgar Varèse, Le Corbusier set out to create a Poème électronique, an electronic poem that combined light, color, images, and sound with the architecture to contain it all. Without a doubt, the innovative methods used to build the pavilion and its semiotic experience form a hugely important part of the Modernist heritage. Still, it is that kind of experience that doesn’t allow the visitor to fully let go and dissolve into. The parallel yet largely unconnected architectural, visual, and acoustic elements create cognitive dissonance by speaking multiple sensory languages at the same time in order to heighten the impact of its content. The structure of the pavilion, for instance, was built to project and reflect sound in a manner that created a sense of various moving sound sources, but its design had otherwise little to do with the experience within. While there were other synaesthetic analogies, such as the electronic nature of the sounds and the geometric shapes of the architecture, it is obvious that the various aspects of the multimedia spectacle were designed mostly independent of each other.

Philips Pavilion at the World’s Fair in 1958 in Brussels, Belgium – © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

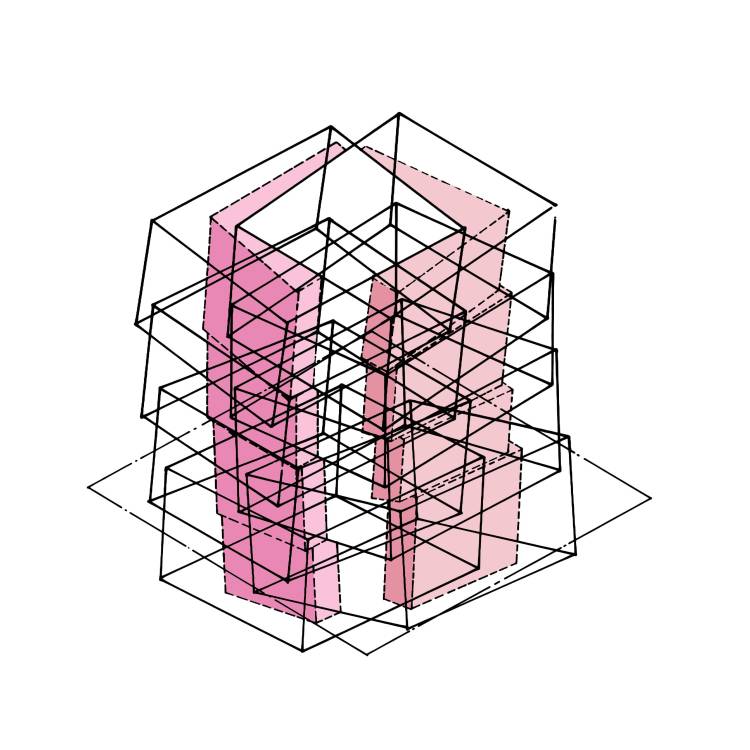

In 1997, Kengo Kuma proposed a similar but much more congruent auditory experience when he was asked to design a memorial for a private company in Japan. Although eventually scrapped, the project was to include a small garden circling a wall that had the names of recently deceased people engraved into it. Upon entering the memorial, the visitor would call out the name of the person they wanted to remember, after which an intricate computer algorithm would convert the sound into overlapping sound waves, creating a distorted echo. This echo would gradually change as more and more tones got dropped from the original name so that, over time, only the person who called it out could recognize it anymore. As the visitor walks through the garden, any noise, such as their footsteps or the rustling of the trees, would get incorporated into the sound. This way, even the slightest changes in the wind or in the person’s stride were immediately reflected in the acoustic feedback. Unlike in the audio-visual extravaganza of the Philips Pavilion, a visitor of Kuma’s memorial would actively engage with the space as they would essentially become one with the memory of their deceased friend or family member. By way of immersion in the soundscape, the lines between past and present become blurred, and the architecture itself fades into the background, creating a truly congruent experience of space and time.

Concept: Memorial Park by Kengo Kuma, Takasaki, Gumma Prefecture, Japan © Kengo Kuma & Associates

Finally, In his 1933 essay “In praise of shadows,” Japanese author Tanizaki Jun’ichirō observes these congruent cross-modal correspondences in everyday life. Notice how by using a black lacquer soup dish instead of a common white ceramic bowl, vision is intentionally impaired in order to heighten the other senses and create a more intimate experience:

“Remove the lid from a ceramic bowl, and there lies the soup, every nuance of its substance and color revealed. With lacquerware, there is a beauty in that moment between removing the lid and lifting the bowl to the mouth when one gazes at the still, silent liquid in the dark depths of the bowl, its color hardly differing from that of the bowl itself. What lies within the darkness one cannot distinguish, but the palm senses the gentle movements of the liquid, vapor rises from within, forming droplets on the rim, and the fragrance carried upon the vapor brings a delicate anticipation… Whenever I sit with a bowl of soup before me, listening to the murmur that penetrates like the far-off shrill of an insect, lost in contemplation of flavors to come, I feel as if I were being drawn into a trance.”

In Praise of Shadows © NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation)

EPILOGUE

In summary, I believe that the modern phenomenon of widespread cognitive dissonance has to do with architecture not being designed for the people who use it but in order to communicate certain intangible ideals or to further someone else’s self-interests. Even if the incentive structures are laid out correctly, that is, somewhere sensible on the spectrum between altruism and capitalist’ practicality, but the methods used aren’t promoting the integration of subject and object, the result will inevitably add to the long list of meaningless objects, that litter most urban environments. As of yet, this analysis hasn’t taken into account the many historical developments that culminated in the status quo. Still, the insights that can be extracted from it can be used to form an elemental framework that provides a practical jump-off point that doesn’t restrict the aesthetic outcome of the project whatsoever. If applied conscientiously, this subject-oriented, time-sensitive, and multi-sensory strategy could be used to build anything from individual homes to infrastructure and even entire cities without imposing any specific style on the architecture.

While the entire argument so far has been grounded in the assumption that we want and need our architecture to have the ability to be anthropomorphized, it is not clear that that is actually the case. Subsequent essays in this series will explore some of the more prominent developments from the late 19th century onwards to gain a better understanding of the extent to which the disagreement about modern architecture is woven into the very fabric of Western culture. Perhaps, at some point, a common middle ground can be found where the residual differences can once again be constructively discussed.

Throughout this essay, I wrote about our physical environment as the anchor to our sense of belonging, safety, and intimacy. As this series progresses, I will expand on this sentiment, occasionally turning away from architectural theory and back towards a much broader expression of human reality. Here, the rudimentary signs and stories of the modern age are replaced by the archetypal images that connect us to an experience beyond space and time. Ironically, as much as they are convinced of their intellectual superiority in matters of psychology and sociology, most architects avoid venturing out this far into the study of the human condition.

I am not looking to prove a point nor establish a hierarchy of architectural styles. I believe that, at the end of the day, what we crave above all is intimacy. As the fundamental condition for love, true intimacy is able to suddenly dematerialize the entire outside world. For the eternity of one moment, space, time, and Self fuse together in the center of the universe. Here, where intimacy meets immensity, nothing exists outside of us, and the slightest sensation of touch, a whisper, or a faint scent sets our whole being on fire. Where there is no difference between matter and meaning, the mind is at ease. And it is exactly in this place where we need to look for inspiration when creating profound architecture.

Cited Sources:

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Eyes of the Skin. Wiley, 1996

- Pollan, Michael. A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams. Penguin Books, 2008

- Venturi, Robert, et al. Learning from Las Vegas. The MIT Press, 1972

- Ansari, Iman. “Eisenman’s Evolution: Architecture, Syntax, and New Subjectivity.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 23 Sept. 2013, https://www.archdaily.com/429925/eisenman-s-evolution-architecture-syntax-and-new-subjectivity

- “Memorial Square World Trade Center 2002 – Eisenman Architects.” Memorial Square World Trade Center 2002 – EISENMAN ARCHITECTS, https://eisenmanarchitects.com/Memorial-Square-World-Trade-Center-2002

- “Nunotani Office Building 1992 – Eisenman Architects.” Nunotani Office Building 1992 – EISENMAN ARCHITECTS, https://eisenmanarchitects.com/Nunotani-Office-Building-1992.

- Steiner, Barbara, et al. Up into the Unknown: Peter Cook, Colin Fournier and the Kunsthaus. Universalmuseum Joanneum GmbH, 2017

- UCL. “Kunsthaus Graz.” The Bartlett School of Architecture, 3 Nov. 2020, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/architecture/research/kunsthaus-graz

- Botton, De Alain. The Architecture of Happiness. Penguin Books, 2014

- Leone, Massimo. “On Insignificance.” The American Journal of Semiotics, vol. 35, no. 1, 2019, pp. 251–268., https://doi.org/10.5840/ajs20175226

- Düchs, Martin, and Sabine Vogt. “The House of the Senses: Experiencing Buildings with Peter Zumthor and Pliny the Younger.” Architectural Space and the Imagination, 2020, pp. 53–65., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36067-2_4

- Kuma, Kengo. Anti-Object: The Dissolution and Disintegration of Architecture. Architectural Association, 2013

- Doshi, Balkrishna V. Writings on Architecture & Identity. ArchiTangle, 2019

- Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Penguin Books, 2014

- Ackerman, Diane. A Natural History of the Senses. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011

- Spence, Charles. “Senses of Place: Architectural Design for the Multisensory Mind.” Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, vol. 5, no. 1, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00243-4

- Bognár, Botond, and Kengo Kuma. Kengo Kuma: Selected Works. Princeton Architectural Press, 2005

- Tanizaki, Jun’ichirō. In Praise of Shadows. Vintage Digital, 2019

You might also like: