Architecture is the poetry of civilization, a dialogue between generations, where human aspirations are etched into stone and timber. As we build, so we remember, and our human presence inscribes itself into the places we inhabit. Architecture thus forms a bridge between past and future that reveals the activities, ingenuity, struggles, and triumphs of those who came before us. Architectural structures are symbolic manifestations of societal evolution, bearing witness to the complexities of the communities that shaped them. This is especially true for buildings of profound historical and cultural significance. Understanding their form and function gives us a glimpse into the broader narrative of human development. As cultures continuously intersect, exchange ideas, and enrich each other’s histories, architecture stands as a tangible record of these interactions, embodying the synthesis of artistic, technical, and ideological influences across time.

“To dwell is to leave traces”

Walter Benjamin

The following essay is the result of a research project held in the summer of 2023 at the Technical University of Braunschweig titled The Roof Structures of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba: Research Through Model-Making (original title: Die Dachwerke der Moschee-Kathedrale von Córdoba Forschung durch Modellbau). For this publication, certain sections have been omitted since they were part of the initial assignment but, in our view, don’t add much value to the discussion of the roof structure. The authors of this essay and makers of the model were E. Taillebois, J. Meyer, and M. Gerber. The course structure was organized around teaching the basic methodological tools of scientific writing and did not provide much guidance on the content of this research.

Title Image © Jesús D. Caparrós Carretero.

Source: La Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba, desde sus tejados, 2023. El Debate.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Conceived as a mosque and later repurposed as a cathedral, the Mezquita of Córdoba has been subject to continuous expansion, modification, and adaptation over the centuries. Today, these transformations render the building a unique architectural palimpsest, offering profound insights into the layered cultural and religious history of Spain. Yet, the very process that has enriched its historical significance complicates efforts to reconstruct its original state. Due to incomplete documentation, tracing the earliest phases of the building — particularly its roof structure — presents considerable challenges. It is at this intersection of uncertainty and architectural investigation that this essay takes its cue.

By dividing the architectural extensions of the mosque between research groups, we sought to deepen our engagement with the reconstruction of distinct historical phases. In our case, the focus lies on the very first construction phase, employing both scientific literature review and research-based model-making to approximate the original roof system. The methodology rests on a comparative analysis of existing scholarly works, hypotheses, and archaeological findings. Before proceeding with the physical reconstruction, we critically assess different sources and examine their internal consistency. Further empirical validation is sought through the study of salvaged components of the original roof.

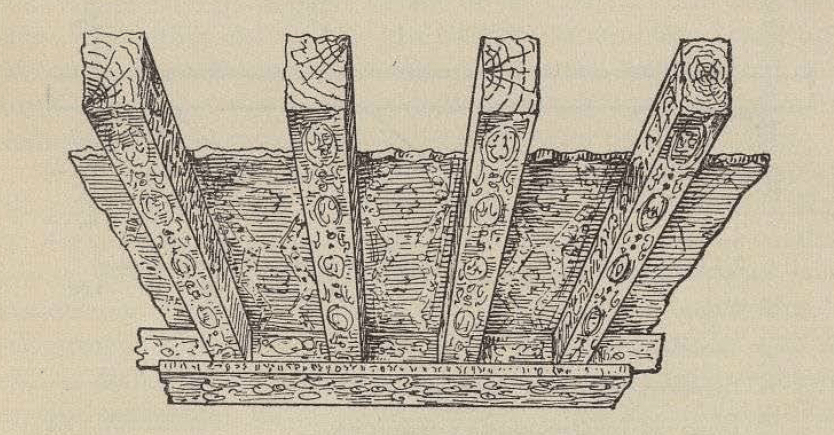

Many of these wooden elements remain within the Mezquita itself, though their locations and functions have often changed over time. The most substantial collection of these is housed within the arcaded gallery of the Orange Tree Courtyard (Patio de los Naranjos), where their construction techniques and ornamentation remain visible. (See Figs. 9 & 10)

To translate theoretical inquiry into spatial comprehension, our model represents a single bay of the main nave at a 1:20 scale. This allows for both an exploration of the spatial impact of different construction hypotheses as well as a tangible engagement with the structural complexity of the roof. Even at this scale, it is possible to critically test and refine assumptions about the original structural logic. The model shows the full height of the Mezquita and maintains a high level of detail to preserve the authenticity of the reconstruction. The interplay between the physical model and its accompanying literary analysis is crucial; they must be understood as a single, integrated body of work.

The following chapters assume a foundational knowledge of the history of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba. A concise overview of its construction chronology and the geopolitical backdrop of each phase shall suffice as an introduction. Thus, chapter 2 outlines the key phases of construction, setting the stage for the central inquiry of this study: the reconstruction of the Mosque’s original roof structure as it existed in the late 8th century. Chapter 3 introduces the specific building segment addressed in our research. Finally, Chapter 4 presents our findings on the roof reconstruction.

The ultimate aim of this research is to refine, and eventually canonize, the understanding of the mosque’s original roof structure—an aspect that remains insufficiently explored to this day.

CHAPTER 2: THE BUILDING

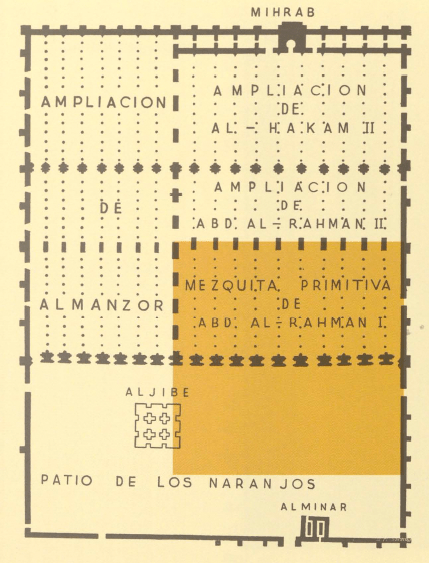

2.1 Construction of the Mosque from 785 to 787 CE (169-170 AH)1

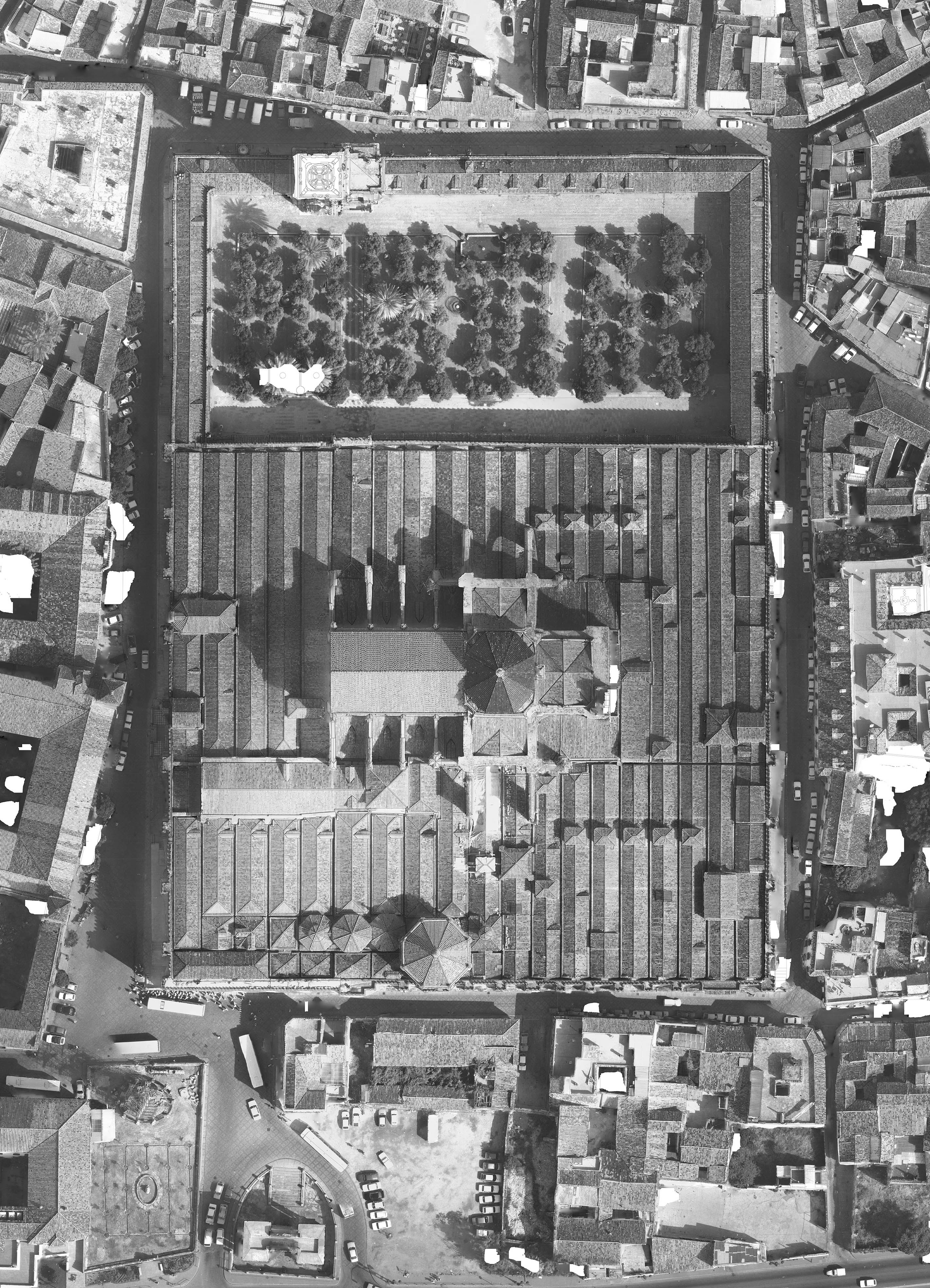

After the Umayyad ‘Abd al-Rahman I declared himself the Emir of the province of al-Andalus in 756 CE (138 AH), he ordered the construction of a mosque between 785 and 787 CE (169-170 AH) to demonstrate his authority and to solidify Córdoba as the capital of the independent western Umayyad center of power.2 Another reason was the rapid increase in the city’s Islamic population during the 8th century. Initially, the Visigothic Basilica of San Vicente had been converted to provide provisional space for Friday prayers. Soon, however, it became too cramped which led to the decision to demolish the original church and construct a mosque on a much more extensive open floor plan.3

Christian Ewert refers to prior examples of early Mesopotamian military cities, such as Kūfa and Wāsiṭ, where the main mosque was also the seat of government serving as both the religious and political center of power. The Cordoban mosque, which now formed the center of the Islamic city,4 was initially nearly square in shape and divided approximately in the middle between the prayer hall and the courtyard. Oriented roughly in a north-south direction, the southern facade measures 79.02 meters on the outside, while the western side measures 78.88 meters. At this point, Manuel Nieto Cumplido cites the work of Félix Hernández Giménez, who observes that the eastern and western sides of the original mosque are not parallel to each other but symmetrically converge toward the north in relation to the axis of the central nave. This results in the interior width of the sanctuary being 33.8 cm wider at the back wall of ‘Abd al-Rahman I’s sanctuary than at the front wall of the courtyard. Similarly, the southern and northern sides are not parallel.5

The total footprint of the complex covers an area of approximately 4925 square meters. According to Nieto Cumplido, the prayer hall, with an area of 2709 square meters, accommodates 5000 worshipers and is already larger than the prayer hall of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, the largest western Islamic sacred building until that point. However, Kairouan’s mosque, with its significantly larger courtyard, which has a total area of 5767 square meters, is still larger than the Cordoban mosque during its first phase of construction.6 Leopoldo Torres Balbás, whose studies are cited by Nieto Cumplido on the same page, describes the prayer hall as measuring 2699 square meters, with a capacity of 10642 worshippers,7 twice the number indicated by Nieto Cumplido. Due to the later publication date and thus a likely broader range of available sources, the information about measurements and capacities will be cited primarily from the work of Nieto Cumplido.

The mosque is oriented roughly northwest-southeast, which does not align with the Qibla, the direction of prayer prescribed in the Qur’an toward the Kaaba in Mecca. According to Torres Balbás, the reason for this misalignment in the Cordoban mosque is that the Qibla wall, and thus the miḥrāb, is oriented toward the south, as was customary in Syrian mosques, where Mecca lies to the south.8

The original building consists of eleven mosque bays with a wider central aisle, whose two-story arcades are covered by eleven parallel gable roofs. Inside, the arcades run over twelve bays toward the miḥrāb at the southern end of the mosque, which would become a widely replicated model and reference work for later Western Islamic architecture.9

The mosque, which was expanded several times over the following centuries, is today not only one of the most significant milestones in Islamic architecture10 but also symbolically represents the peak of Umayyad rule in southern Spain. During this initial phase of construction, the mosque clearly shows a mixture of its Islamic references, specifically the al-Aqṣā Mosque and the Mosque of Damascus, along with early Christian architectural traditions, evident in the use of spolia.11

For a detailed archaeological or architectural analysis of the individual components of the mosque, we recommend the works of Ewert et al., Nieto Cumplido, and Hernández Giménez, as the primary focus of this essay will be on the reconstruction of the roof structure. To this end, a comprehensive recapitulation of the underlying vertical structural elements is only relevant insofar as the ceiling beams rest on the walls built up on the two-story arcade (see Chapter 4).

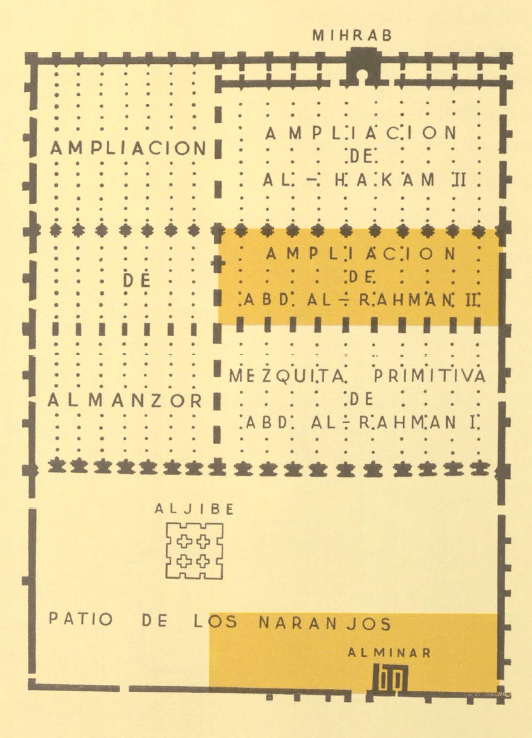

2.2 First Expansion of the Prayer Hall Due to Space Constraints from 833 to 848 CE (219-230 AH)

Under ‘Abd al-Rahman II, the prayer hall was expanded to the south by eight bays in order to create more space inside.12 As a countermeasure to the expansion of the prayer hall by 2018 square meters, the courtyard was also extended by approximately the same area toward the north. At this point, the Cordoban Mosque became the largest Western Islamic mosque and, for a brief period, held the title of the largest prayer hall in the world until its size was surpassed a few decades later by the mosque in Samarra, in present-day Iraq.13

Almost 50 years later, the miḥrāb was transformed from a flat wall niche into an apse adjoining the prayer hall. However, many further details remain unclear due to later alterations.14 Here, Ewert specifically points out that, at this stage of construction, there were no signs of the later-added Qibla transept.15

This type-appropriate expansion initiated a tradition that lasted for over 100 years, where the expansions of the mosque carried out by later Umayyad rulers respected and celebrated the architectural legacy of ‘Abd al-Rahman I. In La vida de los edificios. Las ampliaciones de la Mezquita de Córdoba (1985), Rafael Moneo Vallés writes:

“The formal principles of the Mosque of Córdoba were clearly defined from the beginning and were so definitive that later expansions of the building did not result in radical reconfigurations. The future life of a building is implicitly contained in the formal principles that brought it into being, and understanding them provides us with a clue to understanding its history […] When ‘Abd al-Rahman II wanted to expand the mosque, it was clear: the mosque should grow to the south […] The spatial experience did not change, and the new intervention was integrated without fundamental alterations to the existing space.”16

2.3 Geopolitically Motivated Expansion Starting in 951 CE (340-340 AH)

To strengthen the geopolitical position of Córdoba in relation to the expanding Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa, ‘Abd al-Rahman III assumed the title of Caliph in January 929 CE (317 AH) and planned a comprehensive expansion of the mosque.17 However, under his rule, only the renovation of the northern prayer hall façade and the construction of a larger minaret were realized. The latter, due to its monumental scale, became a symbol of the Caliphate’s power and served as a model for later minarets in al-Andalus and the greater Maghreb.18

2.4 Second Expansion of the Prayer Hall from 961 to 971 CE (350-360 AH)

Under al-Hakam II, successor to ‘Abd al-Rahman III, the prayer hall was expanded to the south by an additional twelve bays, maintaining the previous architectural schema. Notably, this expansion includes a two-bay Qibla transept, which closes the prayer hall transversely and is vaulted with ribbed vaults, as opposed to the usual flat wooden ceilings. Al-Hakam II’s expansion thus incorporates elements from contemporary Abbasid architectural trends while still respecting and continuing the Umayyad building tradition. According to Giese, this duality contributed to the strengthening of Córdoba’s political position against the Fatimids.19

Both Giese’s description and the earlier quote by Moneo Vallés indicate that the second expansion of the prayer hall continues to follow the formal principles of ‘Abd al-Rahman I’s original vision. However, Nieto Cumplido places great emphasis on highlighting this construction phase as a turning point in the architectural impact of the interior:

“The decorative richness, which neither overwhelms nor dazzles, is the embodiment of a magnificent, pure, and clear scheme of thought. It is no longer, as in the first mosque of ‘Abd al-Rahman, an art that is rather improvised and naive, with the rawness of immature fruits, which is captivating precisely because of that and its classical essence. Now we have to deal with a mature, refined, exquisite art, like the Caliph himself who brought it to life. What we have lost of Hellenism, we have gained in magical Eastern values, Mesopotamian accents, in joyful and mysterious contrasts of light and shadow.”20

The extension of the prayer hall by 44.46 meters (internally) to the south created space for an additional 6287 worshippers. Since, for the first time, the courtyard was not expanded along with the prayer hall, the area of the mosque was now divided unevenly. The total usable area after al-Hakam II’s intervention was 13875.75 square meters.21

With the exception of the transept, the roof structure of the extension under al-Hakam II follows the 8th-century construction methods established by ‘Abd al-Rahman I. However, at the beginning of the 18th century, the original coffered ceiling was removed and replaced by vaults, which were largely dismantled again in the late 19th century by Ricardo Velázquez Bosco who replaced them with a metal frame (see Chapter 4.3).22 The original roof structure is, today, some 1200 years later, particularly interesting not only because it has nearly been lost due to numerous modifications but also because generations of Umayyad rulers faithfully continued its tradition despite any inclination towards innovation. This desire to reconstruct the past, which we now recognize as a model and the starting point for many centuries of Islamic architecture, forms the foundation of this essay.

2.5 Final Expansion from 987 to 988 CE (377–378 AH)

Since Prince al-Hisham II, who succeeded al-Hakam II, ascended to the caliphate at the tender age of eleven, the final spatial expansion of the mosque was undertaken under the supervision of the then Chief of Police and Grand Chamberlain, Muhammad Ibn Abī ʿĀmir.24 Fully aware of his influence over the young caliph, Ibn Abī ʿĀmir. exploited his wealth, progressively enticing him into indulgences that, through habit, would evolve into vice. At this point, according to Nieto Cumplido, following prolonged power struggles, the political control over Islamic Spain lay exclusively “in the hands of a dictator as brilliant as he was ruthless, the feared Muhammad Ibn Abī ʿĀmir“.25

The eastward expansion of the mosque included enlarging the prayer hall by an additional eight aisles, accompanied by a corresponding extension of the courtyard. In the course of this transformation, Ibn Abī ʿĀmir deliberately refrained from repositioning the central nave and miḥrāb to align symmetrically with the now nineteen-aisled structure, so as not to openly challenge the authority of the legitimate caliph. Similarly, the Qibla transept was intentionally omitted in the extension, ensuring that the addition remained visually subordinate to the original caliphal mosque of al-Hakam II. The expansion did not introduce significant architectural innovations, as it largely adhered to the construction principles established under al-Hakam II. Moreover, by extending eastward, the interior once again approximated its original, nearly square layout.26 Upon completion, the mosque reached a total area of approximately 22400 m², now accommodating around 40000 worshippers.27

While Ibn Abī ʿĀmir’s decision to maintain the caliphal architectural tradition was likely driven more by political pragmatism than by reverence for continuity, one must nevertheless acknowledge that, by this time, the Great Mosque of Córdoba had already become a true marvel of Islamic architecture—a benchmark against which later structures would be measured for centuries. Today, at least from an architectural perspective, the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba stands as a silent admonition against the modern tendency toward iconoclasm.

CHAPTER 3: SELECTED BUILDING SEGMENT

Since our study focuses on the original roof structure of the mosque, we have limited our detailed analysis to the first two phases of its construction. All subsequent expansions adhere to the rhythm, column spacing, and structural principles established during these initial stages. Even two centuries later, no fundamentally new construction practices were introduced—an indication of the sophistication and enduring influence of the original builders of the Cordoban mosque.

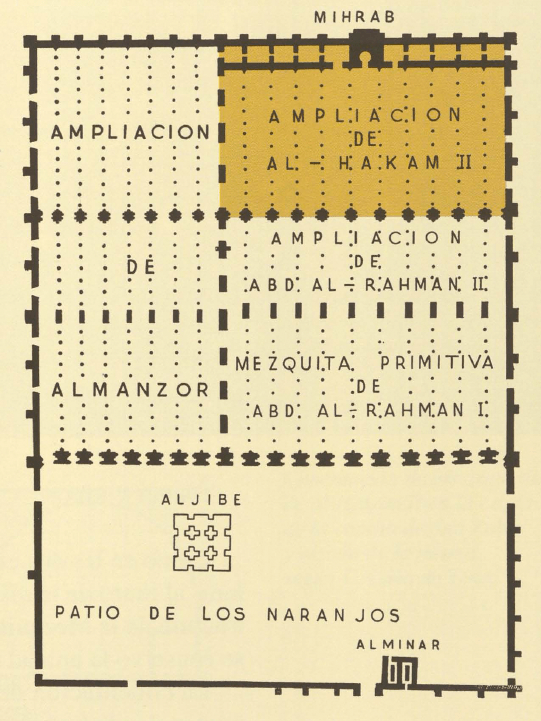

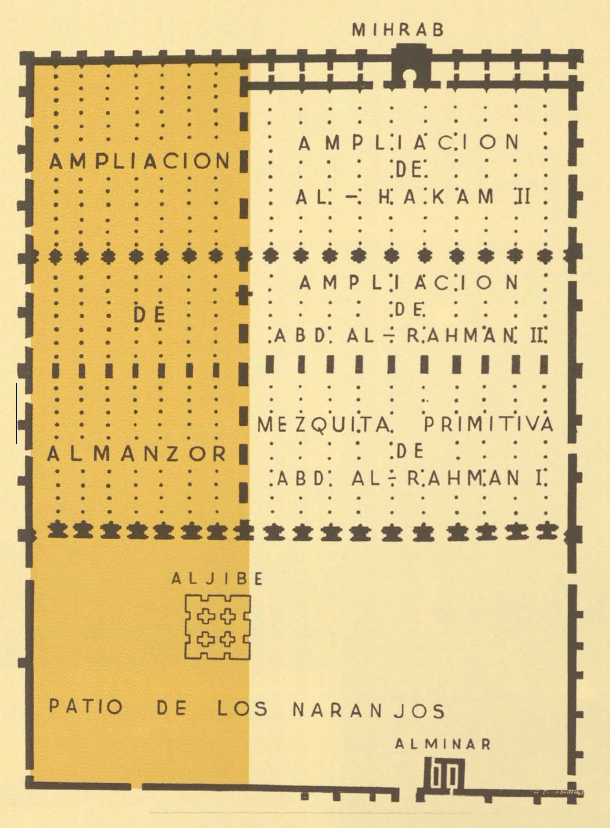

The foundational structure, erected under ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I between 785 and 787 CE (169–170 AH), remained nearly square in plan. Its northern half was occupied by an open courtyard, while the southern half housed the prayer hall, which at that time consisted of eleven aisles and extended approximately 38 meters in depth. The central nave was both wider and taller than the adjacent aisles, with the miḥrāb lying along its southern wall. The prayer hall’s double-tiered arcades, oriented roughly north-south, established a spatial order that would persist despite later modifications. The second construction phase, undertaken about fifty years later, extended the prayer hall southward by eight bays and the courtyard northward by the same measure, without altering the original underlying order. Even the later eastward expansion under al-Ḥakam II, which added eight further aisles, left the position of the central nave and its miḥrāb unchallenged—at the cost of disrupting the hall’s internal symmetry (see Chapter 2.5).

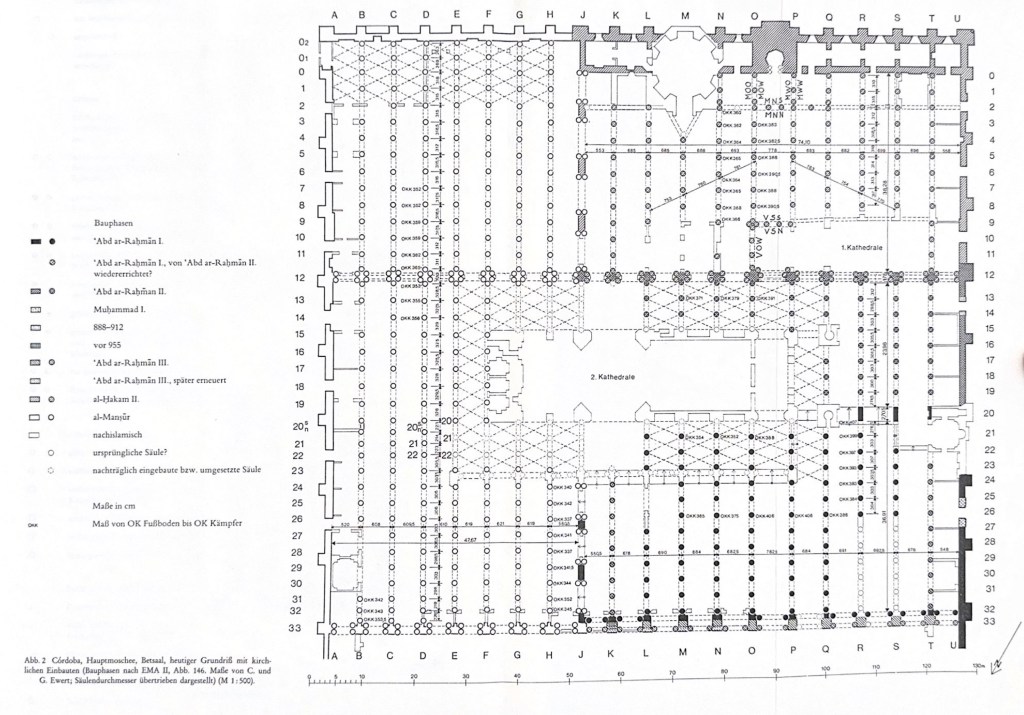

This architectural continuity, along with the significance of the central nave within the structure, led us to examine one of its bays in detail (see Fig. 6). For our model, we selected the seventh bay, counting from the northern wall. Located at the heart of the original structure, it can be regarded as representative of the other bays. Moreover, its ceiling remains unaffected by later vaulting, allowing an unobstructed study of its spatial composition.

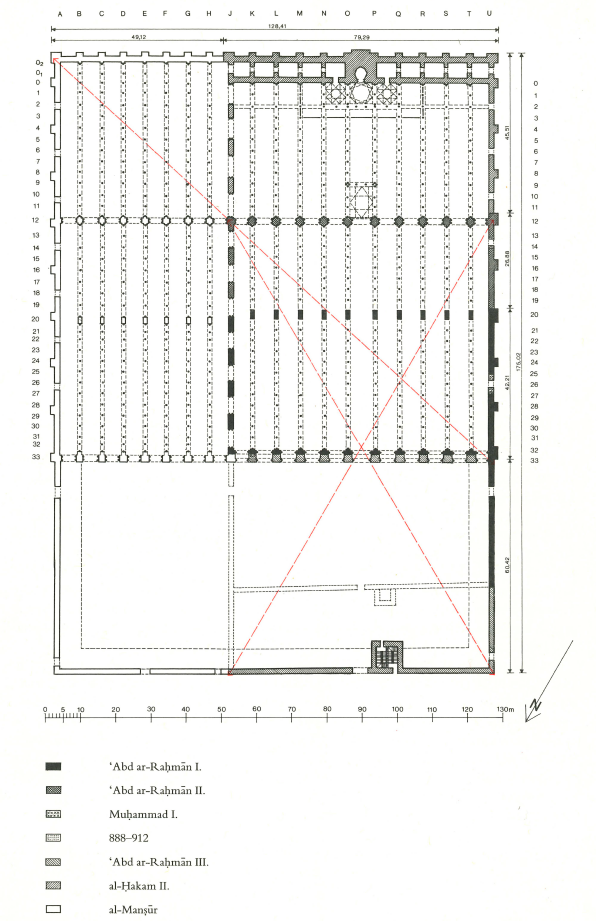

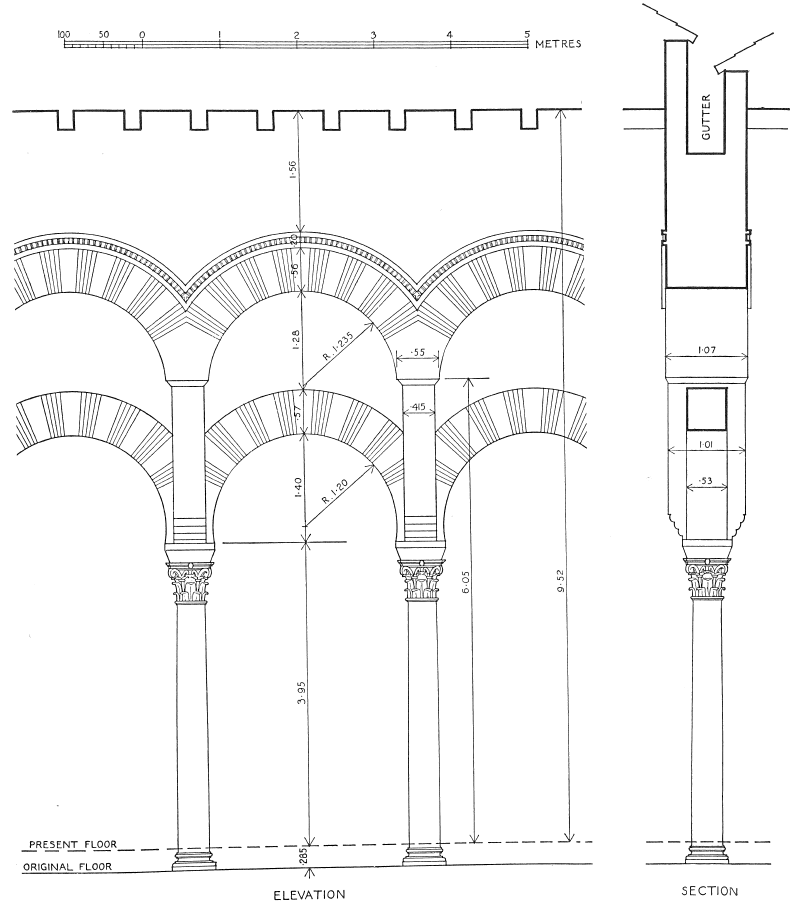

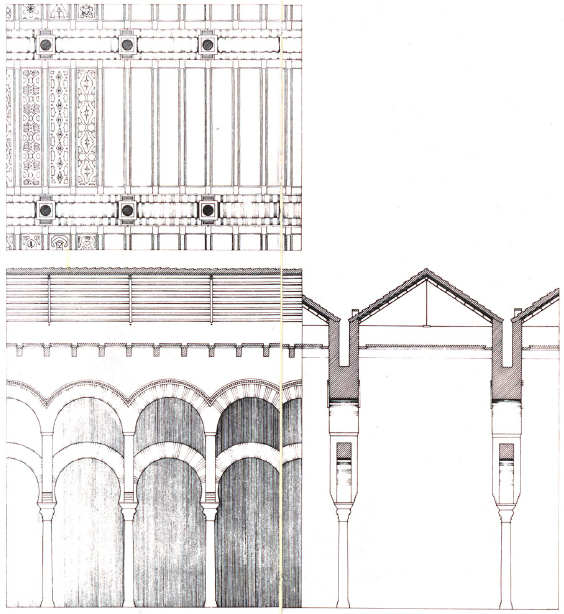

In 1981, Christian Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshack published drawings based on the surveys of Félix Hernández Giménez, from which we were able to derive precise dimensions (see Figs. 7 & 8).27 According to these records, the column spacing along the arcade measures 3.04 meters, while the transverse width of the bay spans 7.825 meters. The columns rest on 28.5-centimeter-high bases, reaching a total height of 3.95 meters, including their capitals and impost blocks. Above them, the first horseshoe arch rises with an internal diameter of 1.20 meters, followed by a second arch at a height of 6.335 meters with a diameter of 1.235 meters. The massive wall above, measuring 1.07 meters in thickness, reaches a height of 9.805 meters, where it meets a corbelled cornice punctuated by beam sockets.

As a consequence of Christian interventions and restoration efforts in the late 19th century, none of the original roof trusses remain intact. Thus, any reconstruction of the initial design must rely on literary references and structural reasoning rather than direct physical evidence. The following chapter will present our hypotheses in detail.

CHAPTER 4: THE ROOF STRUCTURE OF THE MOSQUE OF ‘ABD AL-RAHMAN I

As a result of the numerous expansions under both Islamic and later Christian rule, as well as the ongoing restoration projects beginning in the late 19th century, the Mosque-Cathedral must be understood as a constantly evolving organism when attempting to study and reconstruct its formal and structural character. Such a holistic approach—one that considers the various historical, political, and cultural circumstances shaping its architectural milestones—is fundamental to both an accurate understanding of its construction and the preservation of a certain authenticity in the spatial perception of this sacred edifice.

For our reconstruction of the original roof structure of the Mosque of ‘Abd al-Rahman I., we primarily rely on Spanish-language primary sources, many of which reference Islamic accounts dating back to the 10th century or, as in the case of Félix Hernández Giménez, are based on direct archaeological investigations of the structure. Additionally, the extensive restoration work carried out on the Mosque-Cathedral during the 20th century is comprehensively documented in Sebastián Herrero Romero’s 2015 monograph Teoría y Práctica de la Restauración de la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba durante el Siglo XX.

4.1 Background

The earliest evidence of the original roof structure was discovered in the 19th century inside the expansion of al-Hakam II. This is based on the assumption that the construction techniques used in this section mirror those of the founding structure. During the first third of the 18th century, the coffered ceiling in this area was dismantled, and the walls were raised by 1.20 meters.29 This renovation was necessitated by the deteriorating roofs of the—by then—Christian cathedral, whose original flat coffered ceilings were partially replaced with false vaults made of plaster and reed, reflecting the prevailing Baroque aesthetic of the time. This new architectural style was met with widespread approval among the population and was subsequently applied to the remaining aisles between 1713 and 1723.30

A similar vertical extension of the wall had already occurred at the end of the 15th century during the construction of the rib vaults over the Chapel of San Clemente at the southern end of al-Hišām II.’s expansion. It is believed that this modification was driven both by the curvature of the vaults and the necessity for a deeper drainage channel. This assumption is based on the inadequate capacity of the original gutter, which was found beneath the later masonry additions. Insufficient drainage likely led to the decay of the beam ends due to prolonged exposure to water. In addition, during heavy rains, overflow would have caused water to seep into the interior of the mosque, damaging the wooden elements.31 This conclusion is further supported by the complete renewal of the wooden ceiling when the vaults were installed.32 The climatic differences between the regions also explain why the walls between the aisles, at 1.07 meters, are significantly thicker compared to those in other Syrian mosques.33

During the renovation process, portions of the beams and planks were repurposed for the new roof. Some of these reclaimed beams were first discovered and published in 1841 by the artist and scholar Philibert Girault de Prangey. In 1875, during his restoration work, the architect Rafael de Luque y Lubián uncovered additional remnants of the original coffered ceiling that had been reused in the 18th-century roofing. A few years later, with the removal of the vaults under the supervision of architect Ricardo Velázquez Bosco beginning in 1891, a significant number of original construction elements could be retrieved for the first time.34 In total, 20 beam fragments and 160 planks were recovered, with subsequent analysis confirming that they indeed belonged to the same roof structure.35 Among the recovered elements, six beams and 62 planks featured various decorative carvings, stylistically attributed to the reign of al-Hakam II.36

It is assumed that the roof construction in the final expansion phase closely followed the structural and decorative principles of the earlier annex built under al-Hakam II., which—except for the special configuration of the Qibla transept—adhered to the construction methods of the founding structure. Consequently, any insights gained from the 10th-century roof structure can, with minor adjustments, be extrapolated to the original mosque of ‘Abd al-Rahman I.

In summary, our reconstruction of the original roof framework is based on the architectural elements that were recovered during the 19th century and their analysis by Velázquez Bosco and Hernández Giménez whose research was subsequently revisited toward the late 20th century by Torres Balbás and ultimately expanded upon by Nieto Cumplido.

4.2 Construction

According to Torres Balbás, the original mosque was covered with individual gabled roofs, rather than a flat roof, like the Great Mosque of Kairouan, as initially assumed by Velázquez Bosco. This assumption is supported, among other evidence, by the previously mentioned and indisputable drainage channels on the walls, which, in the case of such a construction, would have collected water from two adjacent gables.37 The fact that the walls above the arcades measure 1.07 meters in thickness in the upper section, thus being highly disproportionate if there were no gutters, also supports the existence of rainwater channels and contradicts the theory of their later addition.

From the assumption of a gabled roof arises the necessity for a truss or purlin roof structure. The beams found during restoration work typically show signs of multiple uses, which complicates precise attribution. Nevertheless, among the findings, there are rafters with beveled ends, as well as tie beams with corresponding cutouts (see Figs. 9 & 10).

Figs. 9 & 10. Recovered beams and rafters, displayed in the Orange Tree Courtyard.

For a long time, there was no consensus about the exact degree of roof pitch. Nieto Cumplido leaned toward a relatively flat gable roof, which would have been hardly visible from the outside.38 Cabañero and Herrera, on the other hand, after examining the cutouts in the beam ends, suggest a much steeper angle. According to them, the original rafters were inclined at 42.8 degrees when resting on the ceiling beams.39 Visually, almost all of the wooden beams exhibited in Córdoba appear to have a similar angle, but verifying this angle with precision was impossible for us.

During the restoration under the direction of Velázquez Bosco, not only were remnants of the original wooden components found but significant insights into the original roof construction were also gained. In addition to the beams studied by Hernández Giménez, with cross-sections measuring 20 x 27 cm, smaller beams with cross-sections of 13 x 21 cm were also found, which fit precisely into the recesses revealed beneath the wall masonry (see Fig. 11). From the analysis of the beam supports, it is concluded that the upper interior surface was a flat coffered ceiling, supported by ceiling beams spaced 85 cm apart.40 Information about the original height of the coffered ceiling varies between sources and location inside the building but seems to have been around 9.50 meters from the original floor which, according to Hernández Giménez’s measurements, is 28.5 cm below the current floor level.41

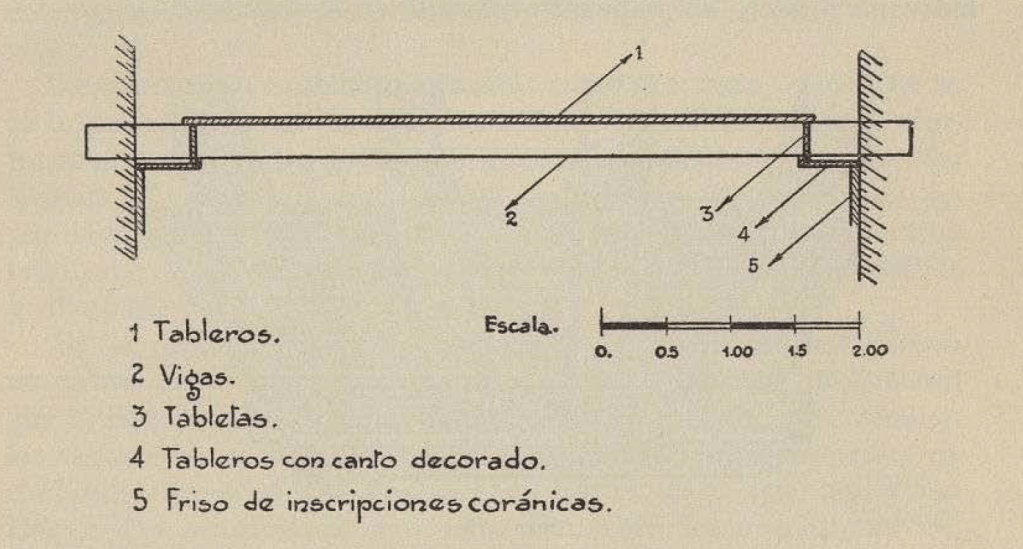

Based on the position in which some of the beams were found, and after thorough consideration of the likelihood of other possibilities, Hernández Giménez concludes that the ceiling structure consists of beams (Spanish vigas) resting transversely across the aisles in the aforementioned recesses of the walls, covered by parallel wooden panels (Spanish tableros).42

The tableros are made of several 33 mm thick pine wood planks, held together on the top with wooden battens (78 x 56 mm) spaced 63 cm apart. The underside of these tableros, like both sides and the underside of the beams, is also richly decorated. In contrast to the beams, the tableros are mostly in excellent condition, with only the ends affected by moisture-related decay, as the high quality of the wood has preserved the rest of the panels. The panels, which range from 76 to 84 cm in width, are composed of either five 16 cm wide boards or four 20 cm wide boards, with some mixed configurations.43

Building on the work of Velázquez Bosco, who did not manage to complete the full reconstruction of the ceiling before his death, Hernández Giménez was able to reconstruct the general structure of the coffers relatively accurately (see Figs. 12 & 13), with the long sides formed by the inner edges of the beams, while the short sides were closed by small boards (Spanish tábicas, tabletás, or tablillas) between the beams. Furthermore, a narrower tablero with a width of 51 cm was found, its decoration extending over a width of 45 cm, precisely matching the length of the undecorated beam ends. Since one long edge of the tablero is also decorated, it is assumed that this must have been visible in the space, with the tablero positioned against the wall with its opposite, undecorated edge. Hernández Giménez places the tablero across and underneath the undecorated beam ends, where it closes with the tábica between the beams, the outer edges of which are about 47 cm from the wall, corresponding roughly to the decorated area of the tablero. According to al-Idrisi, the undecorated edge may have rested on a wooden frieze decorated with Quranic verses.44

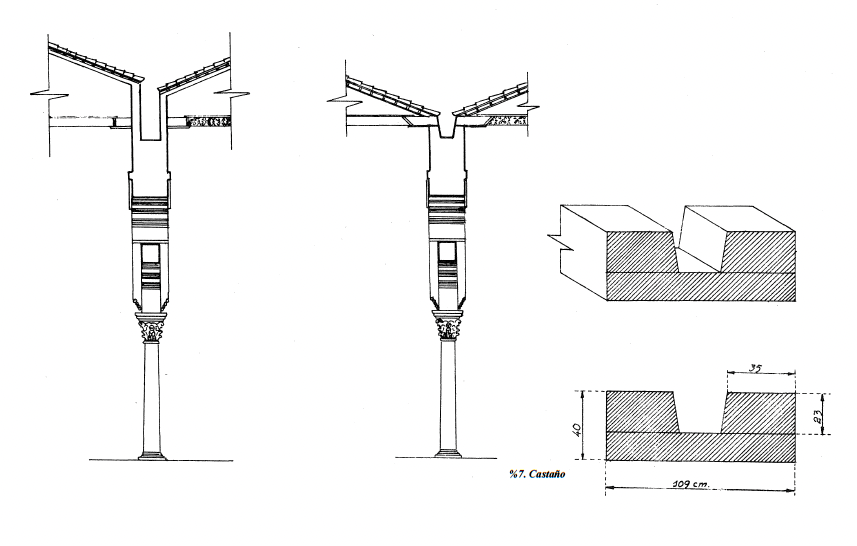

Later, four well-preserved beams were found, each showing a 45° angled notch at the point where Hernández Giménez had proposed the vertical small board. Based on this discovery, Nieto Cumplido was able to adjust the original reconstruction of Hernández Giménez by correcting the angle of the tábica.45 (See Fig. 14.)

According to this new, widely accepted version of the roof, the cross beams of the coffered ceiling form the lower part of a truss, with the rafters representing the two roof planes.46 Therefore, the ceiling over the aisles is not merely a decorative element but also part of the roof’s structural framework—an interpretation that Velázquez Bosco may have shared, though he clearly distanced himself from this idea in his restoration.

While explicit information on the exact structure of the roof truss is scarce, the few remaining clues are sufficient to make well-founded assumptions about the arrangement of the components. For instance, a report by the Cordoban historian Ibn Baskuwal reveals that, at least during the 12th century, the mosque’s roofs were covered with roof tiles.47 Since there is no evidence of a prior structural intervention involving a change in the roof covering or its explicit mention and it has already been argued that the roof construction of the 10th-century expansion was modeled after the founding building, we assume that the mosque of ‘Abd al-Rahman I was also covered with roof tiles.

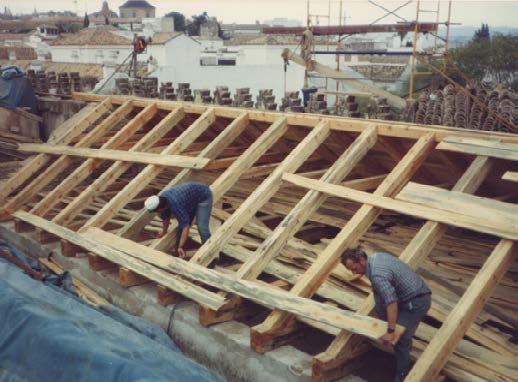

The use of roof tiles implies the need for a substructure to close the rafters within the plane. During his work on the vaults, de Luque y Lubián discovered this substructure in the form of tablazones (singular tablazón), which were made using the discarded tableros from the original coffered ceiling.48 Additionally, several ceiling beams were found, with their decayed beam ends removed, and the usable parts of two beams joined and reused as rafters in the roof truss.49 These shaft connections are visible in some of the beams still preserved today (see Figs. 9 & 10), as well as other notches, which we assume to be the connection points for a collar beam, which would support the rafters at about two-thirds of their length. A similar construction is also visible in photos from a 1990 roof restoration over aisle 1 (see Fig. 15). Although we cannot directly infer the 8th-century construction based solely on recent photographs—especially since all the preserved wooden components have been altered and recycled over time—we consider it likely that the original structure was an ancient form of collar beam roof construction.

Some of the rafters in Figs. 9 and 10 show a double heel offset at the lower end, with which they, as assumed by Nieto Cumplido,50 rested on the ceiling beams, and a smooth cut at the opposite end, which corresponds to the ridge. While no explicit information is available regarding the connection between the ceiling beams and rafters, Herrero Romero specifically refers to a cubierta de par e hilera on two occasions, which refers to a roof structure made of rafters and ridge beam.51 Such a ridge beam would lie between two flat-cut rafters, leading us to conclude, based on the findings, that this was indeed the original construction method of the roof.

4.3 Restoration Work

Following the numerous Islamic expansions and Christian modifications of the Mosque-Cathedral, several restoration efforts from the 19th century onward have also had a significant impact on the building’s current appearance. The most extensive work was carried out under Velázquez Bosco starting in 1981. His efforts to restore the Islamic expression of the building were carried out at the cost of sometimes severe interventions into the original substance. In order to restore the wooden ceiling, parts of the Baroque barrel vaults and gabled roofs were demolished. While some of the oldest, still-preserved roof construction elements were found during this, they were not reused in the reconstruction. Since Velázquez Bosco, at this point, still assumed a flat roof during the initial construction phases, he considered the ceiling and roof as separate systems. The ceiling beams were viewed only as a support structure for the tableros, disregarding their function as tie beams. This assumption necessitated a steel construction for the roof. Additionally, the elevation of the wall atop the double-story prayer hall arcades in order to deepen the rain gutter during the early 18th century was not questioned, despite obvious traces. Thus, Velázquez Bosco was also unable to address emerging questions in the area of the ceiling support zone due to a lack of findings, which led him to noticeably neglect the lateral supports of the ceiling above the arcades in his documentation. Giese refers to these and other misinterpretations as “such a poorly substantiated reconstruction of the original ceiling [that] it would certainly have been more sensible on paper.”52

Some more impartial voices in Spain primarily lament that Velázquez Bosco did not have the opportunity before his death to present his research findings in full, which could have justified his restoration practices.53 Furthermore, the decision to structurally separate the ceiling and the roof and to execute the latter as a steel construction was made as a precaution against the possibility of future fire damage.54 (see Fig. 16 & 17)

For a detailed description of the restoration, we refer to the work of Herrero Romero. However, it can be summarized that Velázquez Bosco likely did not intend to reconstruct the original roof structure but rather aimed to secure the original building components and restore an authentic spatial atmosphere of the building during the Islamic period. While fundamental issues of heritage preservation, such as the handling of materials and construction techniques, as well as the classification and relevance of later historical periods, were neglected, the intention to protect this unique building from irreversible damage in the event of a fire is indeed commendable. We assume that Velázquez Bosco, in his attempt to restore the former splendor of the mosque, acted in good faith but based on incomplete and sometimes incorrect information. Nevertheless, from a historical and architectural perspective, we view Velázquez Bosco’s restoration practices critically. It was only under the supervision of Hernández Giménez that the replacement of original fragments with large-scale replicas ended and thus fundamental aspects of preservation and research regained greater importance in the conservation of the Mezquita.

The project for the restoration of the coffered ceiling, submitted in March 1973 by architect Víctor Caballero Ungría, is primarily based on the previously mentioned archaeological study by Hernández Giménez.55

4.4 Reconstruction Using a Physical Model

The 1:20 scale model offers the possibility of quickly testing various construction variants without having to overly simplify the components. The level of detail allows for the manual assembly of the individual elements, making it easier to understand the construction practices of the time. Additionally, by representing the entire height of the space, the spatial impression can be more accurately conveyed. We set the floor level 28.5 cm lower than the current condition to reflect its original height (see Chapter 4.2), thereby showing the today almost invisible bases of the columns.

For our reconstruction, we use solid wood and wood veneer. On the one hand, this is because the roof structure, which is the focus here, was originally made of wood, and on the other hand, because it maintains a certain aesthetic uniformity without distracting from the roof truss. Nevertheless, we represent the different colors of the stones that form the arcade arches by painting the wood with pigments. As mentioned at the outset, a detailed consideration of the vertical components is not relevant here, so we simplify these significantly. This particularly applies to the column capitals, which were abstracted, disregarding any decorative elements. In choosing the wood, we limit ourselves to soft conifers, mostly pine. The wood barely differs in color and grain, and thus does not set a distracting scale, as some deciduous woods might due to their stronger grain.

Ultimately, it is unclear whether the mosque of ‘Abd al-Rahman I was spanned by ceiling beams with a cross-section of 20 x 27 cm or 13 x 21 cm (see Chapter 4.2). For our reconstruction, we assume the latter, with the cross-section of the rafters corresponding to that of the beams. We do not believe the exact cross-section of the beams and rafters significantly affects the construction, which is why we base the size of the beams on the dimensions of their supports in the wall recesses. Furthermore, both the larger beams (20 x 27 cm) and the tableros are decorated with carvings that date back to the 10th century,56 while the smaller beams (13 x 21 cm) are only decorated with polychrome paintings, dated to the 13th to 14th century.57 Thus, none of the finds originate from the period of the original construction, although the paintings on the smaller beams were likely applied over older Islamic decoration,58 which makes it impossible to date the actual component based solely on its decoration.

We assume that painted wood was used in the 8th century, and only later more elaborate carvings were applied. This is because ‘Abd al-Rahman I built his mosque on the foundations of the Church of San Vicente, which means that the Friday prayer must have temporarily taken place elsewhere during construction. It is likely that the construction period was kept short, which might explain why it was completed in two years, while the first expansion under ‘Abd al-Rahman II took 15 years. Furthermore, initially, only spolia were used, and it was not until the mosque’s expansion that its own Islamic column capitals were produced.59 We believe that a similar approach might have been followed in the decoration of the wooden components, which were initially only painted due to time constraints. Once a mosque for the Friday prayer had been built, there would have been time to pursue more elaborate stonework and woodcarving. Additionally, it seems unlikely that the architectural grandeur of a caliph’s mosque would be subordinate to that of an emir’s mosque.

However, Hernández Giménez seems quite certain that the original coffered ceiling was supported by beams with a cross-section of 20 x 27 cm, a claim that is not explicitly questioned by either Torres Balbás or Nieto Cumplido. Nonetheless, we have doubts, firstly because Hernández Giménez does not mention the smaller beams anywhere, and also because his reconstruction was not always entirely accurate. Secondly, it seems that both beam cross-sections were used at some point and in some places as ceiling beams. As previously mentioned, the dimensions of the beams do not make a significant difference for our reconstruction, so a possible correction at a later time would not be an issue.

The choice of beam cross-section also determines the type of decoration, which is why we have adorned both the beams and the wooden panels (tableros and tábicas) with original patterns that we digitally traced from the recovered fragments, printed, and transferred onto the wood using acetone. The motifs we used on the beams and tableros come from fragments published by Hernández Giménez in his 1928 monograph.60 While these components were found in the Mezquita, they cannot be securely attributed to a specific construction phase. Therefore, the patterns applied in the model represent various carvings and paintings that decorated the ceiling during different construction phases.

We assume that the coffered ceiling completely closed the space and that the decorations on the rafters visible in the photos either come from reused ceiling beams or that the rafters were also decorated, even though they were not visible. The first option seems more logical to us, which is why we leave the rafters undecorated in the model.

The exact position of the connection between the beams and rafters is not documented and cannot be reconstructed due to the poor condition of the beam heads. However, we suspect the position of the notched joint to be slightly in front of the wall, i.e., not immediately inside the wall support. The reason is better accessibility during repairs, such as replacing individual rafters.

According to al-Idrisi, the wooden frieze mentioned in Chapter 4.2, on which the lower part of the coffered ceiling rested was supposedly covered with Quranic verses. However, it is not represented as such in the model, as both the use of religious material and the replacement of Quranic verses with arbitrary patterns seem inappropriate to us. Instead, the outer wall layer is left blanc, corresponding to the plaster layer that is visible in most of the aisles today.

Furthermore, we have omitted a roof covering in our reconstruction because, on the one hand, it is not part of the actual load-bearing structure, and on the other hand, it would obscure the view of the roof truss.

Figs. 18 to 24. Physical model of our reconstruction hypothesis based on previous research of the literature.

CHAPTER 5: SUMMARY

How can we summarize our insights into the roof structures of the Mezquita in Córdoba? Both during the literature review and working with the model, it became increasingly apparent just how challenging it is to make definitive claims. The absence of clear, consistent reports regarding the construction and its components, alongside the scarcity of written sources from the period of Islamic rule in Córdoba, leaves ample room for speculation.

Consequently, in many areas, we have been forced to rely on assumptions, which we have sought to support through a thorough examination of available sources and our own logical inferences. The model-building approach, in particular, allowed us to test and refine our theoretical findings in practice, giving them a tangible foundation.

Whether the details of the roof structure described in this paper can truly be traced back to the founding period of the Mezquita under ‘Abd al-Rahman I in the 8th century or whether later, irreversible alterations were made by his successors remains uncertain.

It is, however, fairly certain that the mosque originally featured eleven parallel gabled roofs rather than a flat roof. Yet, whether the roof pitch was adjusted over time or whether the underside of the ceiling, as we propose, already existed in the first phase of construction, is hard to substantiate. What kind of decoration adorned the beams? Which architectural elements, paintings, carvings, or appliques might have been added later? Since later Islamic expansions and most modern-day restorations consistently adhered to the methods established during the first construction phase, we can reasonably assume that the same applies to the design of the ceiling and roof structure, barring minor variations. Ultimately, our reconstruction, in conjunction with this essay, presents our personal hypothesis about the roof structure of the Córdoba Mosque under ‘Abd al-Rahman I—an interpretation grounded in meticulous, impartial research.

Original authors: M. Gerber, J. Meyer, E. Taillebois

Shortened, reformated, and translated by M. Gerber

FOOTNOTES

- The following events are given according to their Gregorian dates. Other sources may use the Islamic dating system, indicated by AH (After Hijra) or BH (Before Hijra). Giese generally refers to Karl-Heinz Golzio for the dating of specific historical events, particularly his contribution Geschichte Islamisch-Spaniens vom 8. bis zum 13. Jahrhundert in Hispania Antiqua. Denkmäler des Islam by Christian Ewert et al. (pp. 1–52). However, for this essay, referencing Giese shall suffice. ↩︎

- cf. Giese, 2016, p. 21 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, pp. 57-58 ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, p. 70 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 64 ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Torres Balbás, 1982, p. 345 ↩︎

- cf. Torres Balbás, 1982, p. 346 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 22 ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, p. 70 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 24 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, pp. 131-132 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 24 ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, p. 72 ↩︎

- Moneo Vallés, 1985, p. 30. Translated by M. Gerber ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 25 ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, p. 73 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 26-27 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 195. Translated by M. Gerber and S. Olvera Pacheco. ↩︎

- ibid., p. 196 ↩︎

- ibid., p. 249 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 27 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, pp. 279 ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, pp. 78-80 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 285 ↩︎

- Figures taken from Ewert et al., 2009, figs. 2 & 5. ↩︎

- ibid., p. 249. For the specific measurement of the ceiling’s elevation, see ibid., p. 113. ↩︎

- cf. Gómez Bravo, 1778, pp. 757-758. See also Hernández Giménez, 1928, pp. 199-200 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 273 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 249 ↩︎

- cf. Torres Balbás, 1982, p. 538 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, pp. 249-250 ↩︎

- Hernández Giménez, 1928, pp. 193-194 ↩︎

- cf. Torres Balbás, 1982, p. 542 ↩︎

- cf. ibid., 1982, p. 538. ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 74 ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 175 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, pp. 271-273. According to F. Hernández Giménez, the spacing is about 84 cm. See Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 218. ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, Fig. 5. ↩︎

- Hernández Giménez, 1928, pp. 200-205 ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 194-195 ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 206-208 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 273 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 73 ↩︎

- ibid., p. 250 ↩︎

- Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 191 and p. 214 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 273 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 73 ↩︎

- Herrero Romero, 2015, pp. 263 and 280. Translated by M. Gerber ↩︎

- Giese, 2016, p. 314. Translated by M. Gerber ↩︎

- Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 193 ↩︎

- Herrero Romero, 2015, p. 55 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 271 ↩︎

- Torres Balbás, 1982, p. 542 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 74 ↩︎

- Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 273 ↩︎

- Ewert et al., 2009, p. 71 and p. 73 ↩︎

- Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 233 & 241 ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ewert, Christian. “Einführung zu den in den Katalogtexten 1-106 genannten Denkmälern,” in Denkmäler des Islam. Von den Anfängen bis zum 12. Jahrhundert, 5 vols., Hispania Antiqua. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 2009

- Giese, Francine Stéphanie. Bauen und Erhalten in al-Andalus: Bau- und Restaurierungspraxis in der Moschee-Kathedrale von Córdoba. Bern: Peter Lang, 2016.

- Gómez Bravo, Juan. Catálogo de los Obispos de Córdoba, y breve noticia histórica de su Iglesia Catedral, y Obispado: Tomo II. Córdoba: Imprenta de la Viuda de Ocharan, 1778.

- Hernández Giménez, Félix. “Arte musulmán. La techumbre de la Gran mezquita de Córdoba,” Archivo español de arte y arqueología 4, no. 12 (1928): 191–225.

- Herrero Romero, Sebastián. Teoría y práctica de la restauración de la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba durante el Siglo XX. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba, 2015.

- Moneo Vallés, José Rafael. “La vida de los edificios. Las ampliaciones de la mezquita de Córdoba,” Arquitectura: Revista del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid (COAM), no. 256 (1985): 26–36.

- Nieto Cumplido, Manuel. “Aportación arqueológica de las techumbres de la mezquita de Abderramán I,” Cuadernos de estudios medievales 4–5 (1979): 271–273.

- Nieto Cumplido, Manuel. La Catedral de Córdoba. Córdoba: Editorial Almuzara, 1998.

- Ruiz Cabrero, Gabriel. “Dieciséis Proyectos de Velázquez Bosco. La Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba,” Arquitectura: Revista del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid (COAM), no. 256 (1985): 47–56.

- Stierlin, Henri. Architektur des Islam vom Atlantik zum Ganges. Orbis Terrarum. Zürich: Atlantis-Verlag, 1979.

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. “Arte Hispanomusulmán. Hasta la caída del califato de Córdoba,” in España musulmana. Hasta la caída del califato de Córdoba (711–1031 de J.C.), by E. Lévi-Provençal, 331–788, edited by Emilio García Gómez. 4th ed. Historia de España. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1982

FIGURE INDEX

Fig. 1. Aerial View of the Mosque-Cathedral in Córdoba. Source: Almagro Gorbea, Antonio: Mezquita de Córdoba. Ortoimagen cubiertas. https://www.academiacolecciones.com/arquitectura/inventario.php?id=AA-101_03

Fig. 2. Ground plan of the Mosque of Córdoba under ‘Abd al-Rahman I. Source: Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 64.

Fig. 3. Expansion of the Mosque of Córdoba under ‘Abd al-Rahman II. Source: Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 132.

Fig. 4. Expansion of the Mosque of Córdoba under ‘Abd al-Hakam II. Source: Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 195.

Fig. 5. Expansion of the Mosque of Córdoba under al-Hišām II or Muhammad Ibn Abī ʿĀmir. Source: Nieto Cumplido, 1998, p. 282.

Fig. 6. Ground plan of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba after its final expansion (with dimensions based on the work of Félix Hernández Giménez). Source: Ewert et al., 2009, Fig. 1.

Fig. 7. Present-day ground plan of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, including later ecclesiastical additions; column diameters exaggerated for clarity. Source: Ewert et al., 2009, Fig. 2.

Fig. 8. Elevation and section of the roof-bearing elements in the founding structure of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba (with dimensions based on Félix Hernández Giménez). Source: Ewert et al., 2009, Fig. 5.

Figs. 9 & 10. Recovered beams and rafters, displayed in the Orange Tree Courtyard. Source: Elias Taillebois, 2023.

Fig. 11. Traces of the original roof above the wall of one of the naves of ‘Abd al-Rahman I.’s mosque from the 18th century, 1975. Source: ACCC, Material fotográfico, restauración, carpeta 1, n° 62, from Herrero Romero, 2015, Fig. 140.

Fig. 12. Reconstruction of the roof in section by Félix Hernández Giménez. Source: Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 207.

Fig. 13. Reconstruction of the roof in perspective by Félix Hernández Giménez. Source: Hernández Giménez, 1928, p. 208.

Fig. 14. Reconstruction of the roof by Manuel Nieto Cumplido, left: after the raising of the walls, right: original construction. Source: Nieto Cumplido, 1979, p. 272.

Fig. 15. Restoration of the roof of nave no. 1, 1990. Source: Archivo Gabriel Rebollo Puig, from Herrero Romero, 2015, Fig. 164.

Fig. 16. Roof structure of Velázquez Bosco’s reconstruction. Source: Herrero Romero, 2015, Fig. 20.

Fig. 17. Three-panel projection of the restoration under Velázquez Bosco. Source: Ruiz Cabrero, 2015, pp. 48-49.

Figs. 18 to 24. Physical model of our reconstruction hypothesis based on previous research of the literature, 2023. Source: J. Meyer, E. Taillebois, and M. Gerber.

You might also like: